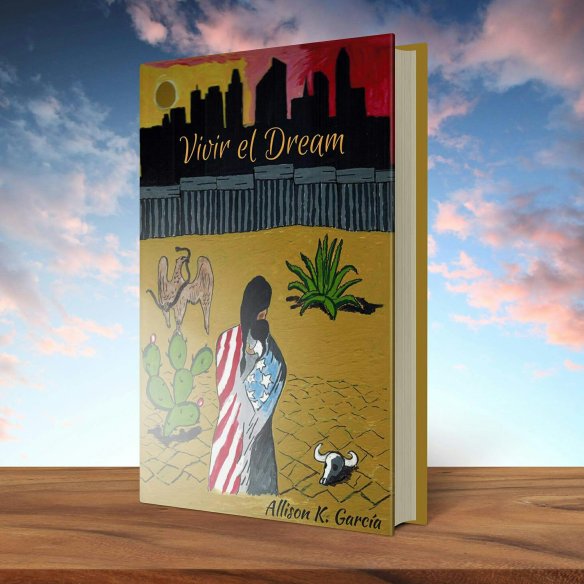

Check out what inspired me to write my book, Vivir el Dream.

Tag Archives: immigration stories

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Norys

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Norys

“Giros” by Norys (fabric art)

- Tell us a little bit about yourself.

My name is Norys, and I’m the oldest of three siblings. I’m also a student of medicine and agricultural engineering. I’ve lived here for almost eight years and am still trying to adapt to the culture and the system in general.

2. What made you decide to do this interview?

I believe it is important so people know who we, the immigrants, are and that we have a voice and story to tell.

3. Where are you from and why did you decide to come to America?

I’m Salvadoran and I didn’t make the decision, my parents did. They thought that here I would have a better future.

4. What was life like for you where you grew up?

Beautiful! Even though there were limitations, we were free. There was not enough food or money. We had meat only on special occasions. I had a lot of friends and every moment with them was like creating a movie. Those are happy memories. What I want to say is that we lived; we lived. It was happier. It didn’t matter if there was no money or if there was no food, it was the spirit of happiness that kept us alive.

5. What is life like for people in your country now? Do you still have family and friends there?

Yes, most of my friends are in El Salvador, my paternal grandparents and my grandmother on my mom’s side and my aunt. It’s still the same, only with the different that it is not the same El Salvador where I grew up; there is more fear, more violence, and more insecurity. It’s still beautiful with its scenery, its culture, and its people, but it’s not the same.

6. What did you have to do to get here (i.e. paperwork, money, etc)?

I crossed the border like most do. It was an unknown and dangerous journey. It took me three weeks to arrive at my destination. You didn’t know if each day that ended would bring another tomorrow. It is like a horror movie. You don’t know what is coming next. It is unknown, horrible. If they asked me to do it again, I wouldn’t do it.

7. What hardships did you face coming to America?

I think that the hardest thing of the journey was everything together, starting from leaving my land. Upon leaving my house, I said, Norys, don’t look back and keep going. So, that was the hardest part, leaving my land, my people. Once I began the journey I was confronted with other difficulties like traveling with strangers. You didn’t really know what type of people were traveling with you, if they were good or if they were bad. There were moments in which I had to console people who wanted to commit suicide and be there and tell them that this was going to pass, that we weren’t going to stay there forever, that it was going to pass. Trying to save my own life and save the lives of others was difficult but it gave me the strength to go on.

(here is a video of the following end of the question, it is in Spanish but you can follow along…the answer starts around 0:15)

One person cut his veins because he didn’t want to leave his grandchildren. And he lost a lot of blood so the guide asked if anyone knew how to put in an IV. And, well, no one is prepared for something like that. In a journey like that it would be really lucky for a doctor or nurse to come, but this time there wasn’t anybody. Seeing the need, and being a student of medicine, I said that I would do it, it was something I had to do. So I said I could do it, I could try. And that person was lying on a dirt floor, and he was white, like paper, and I did the procedure and I don’t know how I did it but I did it, and he lived. He lived and I don’t know what happened with him later but then another woman got like this, like an anxiety, and she got really bad, because the experience, itself, is traumatic. No one is prepared for what comes on the journey. Once on the journey you don’t know how the mind will react. So this person, she said that she didn’t want to live anymore, that she didn’t want to live anymore, but she had two twin daughters that she left behind in El Salvador, and she had told me about them when we met for the first time and had told me that she left behind her family. So I told her, “You have to live. You have to get to this country so you can work and bring your daughters so you can be together, and you can’t think negative. Who will take care of your daughters if you die or if you do something crazy? Who will see after them? So I had my fears, and I had my fears because it was an unknown journey and everyone will tell it differently depending on how they lived it but this is how I lived it. And so I had to put my fears to the side so I could try to be a help to these people and I didn’t mind, I didn’t mind. I lost my fear ad I said, these people need me more, and well, I did that, and I believe that’s what gave me the strength to get through that journey, that uncertain journey, and arrive at the destination. Like the fear of those people helped me to overcome my own fears and therefore be able to help them. You never know when…we all have our fears because it’s a natural thing, right? But seeing that many others were more afraid, then yours becomes insignificant and you can say, “oh, that is nothing, but this is serious. They really need help.” And that’s when you do something, when you give.

8. Once you came to America, what was life like?

My life in the United States. (sigh) It was difficult to adapt, I think it’s like that for everyone. With something new, if you’re afraid, it’s natural. The fear of the unknown. But to me, time passes that you start to adapt and you begin to not be yourself because you have to follow patterns. Like the ones that are already here, they say, “Hey, they do things this way.” Then you follow that same pattern. But after a while you get involved in the system, you change opinions, and you begin adapting your own ways. Another hard thing was learning the language. Going to school when you’re 21 and being around kids that are 14, 15, 16. That was a challenge, but once I arrived here my father told me, “If you going to be in this country, without knowing the language, you’re nothing.” And he was right. I went to school for four years and I graduated with my high school diploma for the second time, and I accomplished it. And now I say, knowing the language has saved my life. It has opened doors for me and I have met a lot of people, I have been to places, that if it weren’t for knowing the language, I don’t know, it never would have happened. Going back to high school and pretending that you’re a certain age when you aren’t is hard. Pretending was hard. For me. But, I had to do it; I had to do it. I’m an introverted person so I got through this time unscathed because I didn’t talk, I only learned and analyzed and observed and I didn’t have the need to say, “Oh, I’m 21 or 22.”

And coming here and being a single mother. To come carrying a baby in your womb and go to school, be a single mother, adapt to the system, a new culture, it was the complete package. It was hard. It was hard but here I am.

9. What helped you get to where you are today?

The worst that can happen to someone is dying. While you’re alive, there are many possibilities, and I believe being 29 years old is a blessing, because in my country, life is no longer worth anything. Then waking up the next day and seeing the light is like, thank you, right? For another day. And to know that everything passes, sadness passes. There will always be a new day. Like I said before, while you’re alive, there are many possibilities. The opportunities are there, it’s only having the desire to look for them. To dream. I am a dreamer and I dream big. I always say, everything happens for a reason. We are here and I am here with a purpose. I am here for a reason. I don’t have everything I want but I have everything I need. You understand? So I think that is what’s most important. Not looking back but rather continuing and continuing and knowing that one day you’re going to be there, where you have always dreamed.

10. How do different generations in your family experience America (i.e. immigrant-born vs. American-born generations)?

The new generations don’t have a sense of culture. When I say that, I feel that they don’t have culture, it is a double culture. Finally, it’s like saying, “Am I American or am I Salvadoran?” What is there in the middle? Then it’s what is there in the middle, it’s what has been lost. The old generations or the older generations, like my parents, my aunts and uncles, cousins, they have that history, they have that folklore still in them, but here they have forgotten to pass it on to these new generations. So it gets lost. They have become Americanized, forgetting about their roots, of that rich folklore that we have as Salvadorans. I’m talking about the rest of my family. Personally, I try to continue cultivating that, that spirit, that culture. I try to cook with those same aromas and pass on that culture to my daughters. And it is difficult when you are married to a person who shares a different culture. Balancing both cultures is hard.

I am trying to continue speaking Spanish, continue cooking those traditional dishes, and continue saving those traditions. In my family I feel it has been lost, because they say, “We are in America, we will live like Americans.” Okay. There’s nothing bad in that but I feel it is important that our children, as Latinos, as the Hispanic-Americans we are, it is important that they know their roots, where they come from. For me it is important, because I want them to have the same feeling, the same love for their roots. It doesn’t matter how nice or ugly El Salvador is. It doesn’t matter how violent it is. That folklore and that human charm will always prevail. It will always be there and just because a group of people are doing bad, doesn’t mean that our children shouldn’t know where their mother and father come from, you know? They have to have that, because it doesn’t matter where they are, if they’re here or in China, they have to know what their roots are.

11. Have you preserved any traditions, foods, languages, or customs from your native country?

Yes. I am writing a book of traditional recipes. I love the kitchen. It is a form of transmitting life and bringing memories. I like cooking and sharing how I do it. Sharing the recipe and say, for example, on holy week, it’s a custom in El Salvador to make fish tortas, and I love them. I remember how my paternal grandmother made them, and I have it etched in my mind and I remember that she would be there in the kitchen and she would said, “Don’t stick your hands in the dough. Don’t touch.” So then I’d only observe but I observed with detail and that how I make them now; it is how I cook. So that’s what I’m doing, preserving, I could say, the recipe as much as the memory, of how I learned to make it and pass it on. Then when I am cooking, I am telling the story, and she was like angry. She didn’t like me to be in the kitchen, but unconsciously I was learning, unconsciously she was teaching. So that is how I learned.

12. How does your cultural heritage affect your views on immigration?

It’s complex. Just the word immigration is like, “ouch.” The system is unjust. Just the fact of crossing borders and adapting ourselves to a culture that’s no our own, is a big change. Aside from that, dealing with a immigration system that doesn’t help, but rather destroys, emotionally and culturally, I think there’s a lot to say and even then it’s not enough.

We aren’t here to be pitied, but it would be good to be accepted for who we are and what we can contribute to the development of the country, bring a little of our culture and share. Originally, this country was built by immigrants. So it doesn’t have a specific culture, if you could say that. There is a diversity of cultures. Why can’t we join each other and celebrate life and celebrate diversity? All of us would be happier and everything would be easier. While we create barriers that you’re white and you’re black, red, yellow, there will always be conflict and nobody will ever be happy. What can’t we all love each other just like we are?

13. What else would you like to share with everyone about yourself, your family, or about immigration in general?

About me?…um…I believe my message would be like this: while you’re alive, there are many possibilities, and it doesn’t mater where we find ourselves. If we are in this place, it’s because we have to be here for a purpose, and independent of what we believe, we have to get out, search, and fight for our dreams. And even though the system or society where we live is unjust, it’s not a reason to say, “I can’t.” Society does not have to accept us. There is a strong reason why we are here “now.” It doesn’t matter where we are. Like I said, the system doesn’t work for us, we don’t have to adjust, but we have to critique and we have to fight. We have to make them know that we have a voice and that we have a story to tell.

Norys, thank you so much for being willing to share so openly about your story.

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Entrevista con Norys

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Entrevista con Norys

“Giros” por Norys (arte en tela)

- Dime un poco acerca de ti.

Soy Norys, y soy la mayor de dos hermanos. También soy estudiante de Ingeniería Agronómica y Medicina. He vivido acá por ocho años, casi, y aún tratando de adaptarme a la cultura y el sistema en general.

2. ¿Por qué decidiste tener esta entrevista?

Creo que es importante para que la gente sepa quienes somos los inmigrantes y que tenemos una voz y una historia que contar.

3. ¿De dónde eres y por qué decidiste venir a los Estados Unidos?

Soy salvadoreña y la decisión no la tomé yo, la tomaron mis padres. Pensaron que aquí podría yo tener un mejor futuro.

4. ¿Cómo era la vida para ti donde creciste?

¡Muy bonita! Aunque había limitaciones, éramos libres. No había suficiente comida o dinero. Comíamos carne sólo en ocasiones especiales. Tenía muchos amigos y cada momento con ellos, es como crear una película. Lo que quiero decir es que vivíamos, vivíamos. Es más alegre. No importa que no haya dinero o que no haya comida, es este espíritu de alegría que nos mantiene vivos.

5. ¿Cómo es la vida para tu gente ahora? ¿Todavía tienes familiares y amigos allá?

Si, la mayoría de mis amigos están en El Salvador, mis abuelos paternos y mi abuela por parte mi mamá y mi tía. Sigue siendo lo mismo, sólo con la diferencia que no es el mismo El Salvador en que crecí; hay más miedo, más violencia, y más inseguridad. Sigue siendo hermoso con sus paisajes, su cultura, y su gente, pero no es el mismo.

6. ¿Qué tuviste que hacer para llegar aquí (como documentos, dinero, etc.)?

Crucé la frontera como la mayoría lo hace. Fue un camino desconocido y peligroso. Me llevó tres semanas para llegar a mi destino. No sabías si cada día que pasaba iba a traer un mañana. Es como una película de terror. No sabes que viene después. Es desconocido, horrible. Si me pidieran que lo volviera a hacer, no lo hago.

7. ¿Qué dificultades enfrentaste viniendo a los Estados Unidos?

Creo que lo mas difícil del camino fue todo en si, desde dejar mi tierra, al salir de mi casa, yo dije, Norys, no mires atrás y sigue. Entonces, eso fue lo más difícil, dejar mi tierra, mi gente. Una vez en el camino enfrenté dificultades como viajar con gente desconocida. No sabías en realidad que tipo de gente estaba viajando contigo, si eran buenos o si eran malos. Hubieron momentos en que tuve que consolar personas que querían cometer suicidio y estar allí y decirles que esto iba a pasar, que no íbamos a quedarnos allí para siempre, que ya iba a pasa. Tratar de salvar a mi propia vida y salvar la vida de los demás, fue difícil pero me dio fortaleza de seguir.

(un video de la siguiente parte de la entrevista)

Una persona se cortó las venas porque no quería dejar sus nietos. Y perdió mucha sangre entonces un guía preguntó si alguien sabía poner intravenosa, suero. Y, pues, nadie está preparado para algo así. En este viaje de esos sería mucha suerte que venga un médico o una enfermera en un viaje de esos, pero esa vez no estaba nadie de ellos. Al ver la necesidad, por ser estudiante de medicina, yo dije tengo que hacer eso, algo que tengo que hacer. Entonces yo dije yo puedo hacerlo, lo puedo intentar. Y esa persona estaba tirado en un piso de tierra y estaba blanco, como un papel, y le hice el procedimiento y no sé como pero lo hice y vivió. Vivió y no sé que pasó con él después pero otra señora entró en esta, como una ansiedad, y se puso mal, porque la experiencia, por si misma, es traumática. Entonces uno no está preparado por lo que viene en el camino. Entonces una vez en el camino no sabe como la mente va a reaccionar. Entonces esta persona ella decía que ya no quería vivir, que ya no quería vivir, pero tenía dos niñas gemelas que dejaba en El Salvador y ella me lo había comentado cuando nos conocimos por primera vez y dijo que dejaba su familia. Entonces yo le dije, “Tú tienes que vivir. Tienes que llegar a este país para trabajar y traer tus niñas para estar juntas y no puedes pensar negativo. ¿Quién va a cuidar tus niñas si te mueres o si cometes una locura? ¿Quién va a ver por ellas? Entonces yo tenía mis miedos, y yo tenía mis miedos porque es un camino desconocido y cada quien lo va a contar diferente a como lo vivió pero esto es como yo lo viví. Y entonces yo tuve que poner mis miedos a un lado para tratar de ser de ayuda para esta gente y no me importó, no me importó. Perdí el miedo y yo dije esta gente me necesita más, y pues, hice esto, y creo que eso fue lo que me dio fuerza para pasar ese camino, ese camino en cierto, y llegar al destino. Como el miedo de esas personas me ayudó a vencer mis propios miedos y así poder ayudarles. Nunca se sabe cuando…todos tenemos miedos porque es algo natural. ¿Verdad? Pero al ver que muchos de eses otros tienen más miedo, entonces lo tuyo se vuelve insignificante y puedes decir, “ah, eso no es nada, pero esto si es serio. Ellos si lo necesitan.” Y es cuando haces, cuando das.

8. Ya estando en Estados Unidos, ¿cómo fue tu vida?

Mi vida en los Estados Unidos. (suspira) Fue difícil adaptarme, creo que como a todos. Con algo nuevo si tienes un temor, es natural. El temor de lo desconocido. Pero a mi me pasa el tiempo que adaptas y no empiezas a ser tu mismo porque tienes que seguir patrones. Como los que ya están acá entonces dicen, “Ay, ellos hacen esto.” Entonces sigues este mismo patrón. Pero a medida te involucras más en el sistema, vas cambiando opinión, y vas adaptando, que adaptes a tus propios medios. También creo que algo difícil fue aprender el idioma. Ir a la escuela cuando tiene 21 años y estar alrededor de jóvenes que tienen 14, 15, 16 años. Eso fue un reto, pero al llegar acá mi papá me dijo, “Si vas a estar en este país, sin conocer el idioma, ya no hicistei nada.” Entonces él dijo, “Tienes que aprender el idioma para poder sobrevivir en este país.” Y él estaba en lo correcto. Fui a la escuela por cuatro años y me gradué de bachillerato por segunda vez y lo logré. Y ahora digo, saber el idioma ha salvado mi vida. Me ha abierto puertas y he conocido mucha gente, he conocido lugares, que si fuera por el idioma, no sé, nunca hubiera pasado. Volver al bachillerato (Allison pregunta: “¿Bachillerato quiere decir high school?”). Sí, volver al high school y pretender que sos una persona, que tenés una edad cuando no lo sos, eso. Pretender fue difícil. Para mi. Pero, lo tenía que hacer; lo tenía que hacer. Soy una persona introvertida entonces pasé ilesa esta etapa porque no hablaba, sólo aprendía y analizaba y observaba y no había necesidad de decir, “Ah, tengo 21 años o tengo 22.”

Y llegar acá y ser madre soltera. Venir cargando una bebé en el vientre e ir a la escuela, ser madre soltera, adaptarse al sistema, a una nueva cultura, fue un paquete de completo. Fue difícil. Fue difícil pero aquí estoy.

9. ¿Qué te ha ayudado llegar a dónde estás hoy?

Lo peor que puede pasar a uno es morirse. Mientras está vivo, las posibilidades son muchas, y creo que tener 29 años es una bendición, porque en mi país la vida ya no vale nada. Entonces despertar el siguiente día y ver la luz es, like, gracias, ¿verdad? por otro día. Y saber que todo pasa, las tristezas pasan. Siempre va a ver un nuevo día. Como dije anteriormente, mientras está vivo, las posibilidades son muchas. Las oportunidades están allí, sólo es tener el deseo de buscarlas. Soñar. Soy una soñadora y sueño en grande. Yo siempre digo, todo pasa por una razón. Estamos aquí y estoy aquí con un propósito. Estoy aquí por una razón. No tengo todo lo que quiero pero tengo todo lo que necesito. ¿Entiendes? Entonces pienso que eso es lo más importante. No mirar atrás sino seguir y seguir y saber que algún día vas a estar allí donde siempre has soñado.

10. ¿Cómo experimentan las generaciones diferentes en tu familia los Estados Unidos (como los que nacieron en tu país comparado con los que nacieron en los Estados Unidos)?

Las nuevas generaciones no tienen el sentido de cultura. Cuando digo eso, siento que no tienen cultura, es una cultura doble. Entonces al final, es como decir, “¿Soy Americano o soy salvadoreño?” ¿Qué hay en el medio? Entonces es lo que hay en el medio, es lo que se ha perdido. Las generaciones viejas o las generaciones mayores, como mis padres, mis tíos, primos, ellos tienen esa historias, ellos tienen ese folklor todavía en ellos, pero que acá han olvidado pasar a estas nuevas generaciones. Entonces se pierde se han vuelto más americanizados, olvidándose de sus raíces, de ese folklor rico que tenemos como salvadoreños. Estoy hablando por el resto de mi familia. En lo personal trato de seguir cultivando eso, ese espíritu, esa cultura. Trato de cocinar con esas mismas aromas, de pasar esa cultura a mis hijas. Y es difícil cuando estás casada con otra persona en que comparte diferente cultura. Balancear ambas culturas es difícil.

Tratar de seguir hablando el castellano, seguir cocinando esos platos típicos, y seguir guardando las tradiciones. En mi familia siento que se ha perdido, porque dicen, “Estamos en América, vamos a vivir como americanos.” Está bien. No hay nada de malo en ello pero siento que es importante que nuestros hijos e hijas, como latinos, como hispanoamericanos somos, es importante para ellos que sepan sus raíces, de donde vienen. Para mi es importante, porque yo quiero que ellos tengan ese mismo sentido, ese mismo amor por sus raíces. No importa que tan bonito, feo, sea El Salvador. No importa cuan violento sea. Ese folklor y ese carisma humano siempre va a prevalecer. Siempre va a estar allí y sólo porque un grupo de personas estén haciendo mal, no significa que mis hijos no van a saber de donde su mamá viene o de donde su papá viene, ¿entiendes? Ellos tienen que tener eso, porque no importa donde estén, si aquí o en la China, ellos tienen que saber cuales son sus raíces.

11. ¿Has preservado algunas tradiciones, comidas, idiomas, o costumbres de tu país natal?

Sí. Estoy escribiendo un libro de recetas tradicionales. Me encanta la cocina. Es una forma de transmitir amor y traer recuerdos. Me gusta cocinar y compartir como lo hice. Compartir la receta y decir, por ejemplo, por semana santa, se acostumbren en El Salvador hacer tortas de pescado, y me encantan. Recuerdo como las hacía mi abuela paterna y la tengo muy grabado y recuerdo que estaba allí en la cocina y ella decía, “No metás las manos en la masa. No toqués.” Entonces yo sólo observaba pero observaba con detalle y es como yo la hago ahora; es como la cocino. Entonces a eso voy, a preservar, por decirlo, la receta como la memoria, de cómo aprendí a hacerla, y pasarla. Entonces cuando yo estoy cocinando, yo estoy contando la historia, y ella era como enojada. No le gustaba que yo estuviera en la cocina, pero inconscientemente estaba aprendiendo, inconscientemente ella me estaba enseñando. Entonces así es como yo aprendí.

12. ¿Cómo afecta tu herencia cultural tus ideas sobre la inmigración?

Es complejo. Solo la palabra inmigración es like “ouch.” El sistema es injusto. Con solo el hecho de cruzar fronteras, y adaptarnos a una cultura no propia es un cambio grande. A parte de eso, lidiar con un sistema de inmigración que no ayuda, sino que destruye emocionalmente y culturalmente, pienso hay mucho por decir y aún no se suficiente.

No estamos aquí para mostrar lástima, pero será bueno ser aceptados por lo que somos y lo que podemos contribuir al desarrollo del país, traer un poco de nuestra cultura y compartir. Originalmente este país ha sido construido por inmigrantes. Entonces no tiene una cultura específica, por decirlo así. Hay una diversidad cultural. ¿Por qué no unirnos y celebrar la vida y celebrar la diversidad? Todos seríamos más felices y todo sería más fácil. Mientras creamos barreras de que vos sos blanco, que vos sos negro, rojo, amarillo, siempre va a ver conflicto y nadie va a ser feliz. ¿Por qué no nos queremos todos así como somos?

13. ¿Qué más te gustaría compartir sobre ti, tu familia, o sobre inmigración en general?

¿Sobre mi?…um…creo que mi mensaje sería: mientras estás vivo, las posibilidades son muchas, y no importa donde nos encontremos. Si estamos en este lugar, es que allí tenemos que estar por un propósito, y independientemente en lo que creamos, hay que salir, buscar, y pelear por nuestro sueños. Y aunque el sistema o la sociedad donde vivimos sea injusta, no es razón para decir, “No puedo.” La sociedad no tiene que aceptarnos. Hay razones fuertes por la que estamos aquí “ahora.” No importa donde estemos. Como dije, el sistema no trabaja para nosotros, no hay que acomodarnos, pero hay que criticar y hay que pelear. Hay que hacerles saber que tenemos voz y que tenemos una historia que contar.

Norys, gracias por estar dispuesta compartir tu historia tan abiertamente con nosotros.

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Una Entrevista con Alba Guevara (versión en español)

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Entrevista con Alba Guevara

1. Dime un poco acerca de ti.

Okay, mi nombre es Alba. Tengo tres hijos. Soy de Honduras. ¿Qué más puedo decir? Trabajo. Soy mamá soltera. Me gusta pasar tiempo con mi familia, con mis hijos. Me gusta estar en casa. Adoro estar en casa. Me gusta salir a mi pasatiempo, salir de compras, (se ríe) pero ya no lo hago. Y me gusta la playa, eso es lo que más me gusta, aparte de hacer las compras, y eso, pasar tiempo con mis hijos.

2. ¿Por qué decidiste tener esta entrevista?

Porque me gusta compartir cosas mías. Tal vez otra gente está en la misma situación mía o ha pasado lo mismo que yo, y, pues, no sé, no lo dicen o no lo pueden decir. Y, por eso.

3. ¿De dónde eres y por qué decidiste venir a los Estados Unidos?

Soy de Honduras y la decisión de venir acá no fue precisamente mía, pues, mi mamá. Yo no lo sabía, que venía para acá. Y un día ella me dijo que mi hermana quería hablar conmigo, que le llamara a mi hermana y hablé con ella y ella me dijo tal fecha. Era como, faltaba, no sé, un mes, o yo no recuerdo cuando, y ella me dijo, “Esta fecha, el 16 de septiembre, voy por ti a Guatemala. Alístate, que yo te recojo allí.” Pues, yo había querido venirme para acá cuando estaba bien pequeña, como de 13 años. Mi hermana había ido para allá pero mi mamá no me dejó venir en este tiempo. Y cuando ya estaba embarazada de Nohelia, ella me habló a mi hermana que fuera por mi. Y eso fue por lo mejor, haberme venido.

4. ¿Cómo era la vida para ti donde creciste?

Pues, fue difícil, bastante difícil, pero en comparación con los vecinos que teníamos, era diferente a la de nosotros. Ellos estaban en peor situación a la que yo me crecí. Bastante difícil pero a comparar con los vecinos, pues, no era tanto, pero decidí, pues, no lo decidí yo, fue mi mamá que decidió que viniera. Pues, estaba embarazada y ella me dijo, “Te vas para allá.” Y pienso que fue lo mejor porque nació Nohelia acá y no sé que hubiera pasado si ella hubiera nacido allá. Quizás me hubiera venido y ella se hubiera quedado y no la hubiera podido traer. Quizás hasta que yo pudiera hacer mis papeles ella hubiera podido entrar años después. Eso fue bien, haber venido cuando estaba embarazada yo de ella.

5. ¿Cómo es la vida para tus paisanos ahora? ¿Todavía tienes familiares y amigos allá?

Sí, están mis papás. Hay más familia, bastante familia, por parte mis papás. Las personas de Honduras son bien pobres, eso sigue igual. Nada ha mejorado. Es un país muy atrasado, muy pobre, y cada vez que voy para allá es bien difícil porque ya no me gusta. No me acostumbra estar allá, me desespera estar allá. Y, no sé, me acostumbré vivir acá. La vida acá es diferente. Compararla con la de allá, está más cómodo, estar aquí. Pues, hay que trabajar bastante pero es más seguro. La seguridad es mucho mejor acá que allá.

6. ¿Qué tuviste que hacer para llegar aquí (como documentos, dinero, etc.)?

Bueno, dinero, porque papeles no tenía. Entré ilegal. En este tiempo, ’96, entré ilegal acá. A comparación con otras personas que han entrado, lo mío no fue tan difícil porque mi hermana me trajo. Me recogió en Guatemala y con ella vine. No pagamos ningún coyote, ni nadie, sólo íbamos nosotros dos. Pues ella buscó ayuda allá en todo lo que fue el viaje de México, que le dieran direcciones las personas. Viajábamos en un carrito pequeño y ella le pagaba a alguien que nos llevara a tal lado por direcciones y todo. Pues, no fue tan malo. Yo venía embarazada y a pesar de todo eso, el viaje no fue tan malo. No caminé y fue muy seguro porque no me vine con coyote, que eso es tan peligroso. Yo no caminé nada y vine en carro con mi hermana hasta que llegamos a la frontera. Ella se vino porque era el tiempo de que tenía su boleto que tenía que entrar por California, y me dejó allí con la suegra de ella, la suegra de mi otra hermana, y luego allí me pasaron, unos muchachitos me pasaron. No fue tan difícil. Siento que en ese tiempo fue fácil, y ahora está difícil. Hace 18 años atrás pienso que no era tan difícil. Ahora está peligroso, más peligroso que en este tiempo. No sé cuanto dinero pagaron ellas por que me pasaron, yo no pagué nada. Ellas, mis hermanas, pagaron por mi. Ellas hicieron eso por mi.

7. Ya estando en Estados Unidos, ¿cómo fue tu vida?

Recién llegué, fue difícil, porque lo principal, pues, no tenía papeles, embarazada, y luego nació mi niña a la semana de estar aquí. La semana de haber llegado nació ella y muy difícil. Cuando llegué a California fue muy difícil porque no pude obtener el seguro médico, ni para mi, ni para ella, para mi parto. Ella nació y me lo negaron. Entonces luego me mudé a Nueva York, a los tres meses de ella haber nacido. Cuando me mudé a Nueva York, allí cambiaron ya las cosas. Allí empecé a trabajar y cambió bastante. Encontré más ayuda para las personas ilegales en Nueva York. Siento que en este estado ayudan mucho a las personas que no tienen papeles. Y estaba así, ilegal, sin papeles, y allí pude obtener ayuda para mis gastos, como darle a comer a mi niña. Me dieron asistencia pública. En California no pude tener ni el Medicaid. En Nueva York me dieron todo eso. Sentí que allí fue más fácil y no pude vivir en California por esa razón. En Nueva York me facilitó más las cosas.

8. ¿Qué te ha ayudado llegar a dónde estás hoy?

En especial, quien he tenido mucho apoyo es una de mis hermanas, mi hermana mayor. Fue la que me fue a traer a Honduras. Es la que siempre está pendiente de mi en todo, aún cuando me separé. Económicamente me ha ayudado en mucho. Ella está muy pendiente de mi. Cuando estoy indecisa de tomar una decisión de algo, ella me da ideas y me dice, “¿Tú crees que eso sería bien?” Ella me apoya. De la familia, de las hermanas, ella es la más fuerte. Ella ha pasado muchas cosas. Ella es la que siempre da la cara por todo. Es la que siempre, cuando pasa algo en la familia, es la que siempre estamos hablándole para algo. Y ella apoya en todo. Ella es una de las personas que ha motivado a mi cuando yo he estado tristeza, derrumbada. Ella me habla y es un gran apoyo. Y mis hijos, que son los motores de mi vida.

9. ¿Cómo experimentan las generaciones diferentes en tu familia los Estados Unidos (como los que nacieron en su país comparado con los que nacieron en los Estados Unidos)?

Pues, es muy diferente, mucha diferencia. Cuando uno se crece allá, es otro tipo de enseñanza, otra cultura, muchas cosas. Aquí los niños tienen más; eso es lo que yo he visto. Están más libre de expresarse, no son como más sumisos, están con más libertad. Los niños, no sé, se crecen mejor acá. En todo, porque a como me crecí allá, como mis papás se crecieron, es mucha la diferencia. Cuando fui con mis hijos a Honduras, ellos ven todo lo que se ve allá, que se quedan asustados por lo que ven, por lo que hay, la pobreza que hay, la diferencia. Él fue, el varoncito, y él sí le gusta jugar fútbol. Él tuvo que quitarse sus zapatos, sus tacos, para jugar como los demás niños porque ellos no tienen tacos para jugar. Y él lo quiso hacer así también porque no iba a jugar él con zapatos, con tacos, cuando los niños no tenían. Eso es una de las cosas que él vio, que no tienen zapatos. Él dice que no tenían ropa para vestirse, dos mudadas que traerse mas nada. Eso es mucha diferencia a lo que es aquí a lo que es allá. La comida que allá no es tan abundante, y aquí, pues, sobra la comida. Pienso que, no sé, hay gente que dice que aquí aguantan hambre pero yo pienso que no, porque aquí si uno va a una iglesia, le regalan comida. Yo pasé por hambre recién que me separé. No se me va a olvidar. Pasamos dos semanas sin comida, sin nada. Yo fui a la iglesia que está acá y allí me regalaron comida. Fue difícil, dos semanas sin tener nada que comer nosotros en casa aquí, nada. Pero a mi me regalaron comida y eso nos alcancemos. Pero comparado a la hambre que se pasa allá, que es hambre, hambre de no haber nada, no se compara.

10. ¿Has preservado algunas tradiciones, comidas, idiomas, o costumbres de tu país natal?

Sí, hablamos español aquí en casa siempre. Es muy poco lo que hablamos en inglés. Las comidas lo comemos como allá. Yo acostumbré a hacer la comida, la comida que comemos en Honduras, como los frijoles, el arroz, así como comemos allá. Tortillas yo no como pero los niños sí comen. Comemos el queso, la cuajada, la mantequilla, y la comida igual como la cocinaba yo allá. Los guineos verdes, los plátanos. Para nosotros es diferente los guineos con los plátanos, son dos cosas diferentes. Plátanos maduros o verdes, o los guineos verdes, es lo que comemos, tajadas. Eso siempre lo acostumbré en casa hacer; no cambiamos nada. Las tradiciones. Como lo que hace para semana santa, nosotros acostumbramos a comer pescado seco para semana santa, eso lo hago siempre. Para Navidad hago tamales, es lo que se acostumbra hacer allí en Honduras, y la comida que hacemos para en ese tiempo, eso siempre lo sigo haciendo.

11. ¿Cómo afecta tu herencia cultural tus ideas sobre la inmigración?

En lo que está pasando y que ha pasado siempre acerca de la inmigración, porque uno se viene, tomar la decisión de venirse, arriesgarse. Incluyendo las personas que traen a sus niños pequeños y que traen a arriesgarlos, a lo que pase, las cosas, que les pase algo. Pero yo veo que es por necesidad, que lo traen porque la vida en Honduras no es fácil. Y tal vez en otros países también, no sólo en Honduras sino otros países, y ellos están trayendo a sus hijos porque quieren algo mejor para ellos. Y si los traen para acá, ellos acá estarán mejor y estarán con sus familiares, estarán más salvos. Y eso está malo de que las personas piensen todo lo contrario, de que tal vez vienen los niños de allá que tal vez vienen a hacer las cosas que no deben de hacer acá, que son personas que no son buenas para vivir en este país. Pues, no siempre eso es cierto, no todas las personas somos iguales, siempre hay de todo, y la mayoría vienen por necesidad, por buscar algo mejor, para la vida de esas criaturas. Pienso que todos merecemos una oportunidad y una mejor vida, y están buscando algo mejor para esos niños.

12. ¿Algo más que te gustaría añadir al fin de la entrevista?

Hacer conciencia a las personas, de que la vida en los países de uno no es fácil. Es muy diferente a las personas que vivimos acá o que tal vez nunca han vivido fuera de acá, que no han pasado problemas, de necesidades como de hambre, de peligro. Es muy difícil tal vez en lo que hemos crecido en otros países, en países muy pobres como Honduras. Sabemos lo que pasa allá, como se vive allá, lo difícil que es para poder sobrevivir con tanto peligro, con tanta hambre, tanta necesidad. Es diferente, ¿verdad? La otra cara de la moneda allá, acá, y tal vez hay personas que no saben nada de eso, tal vez piensen todo lo contrario porque no han vivido lo que uno ha vivido, lo que uno ha pasado. Y pienso que por eso esos piensan de esas formas. Todos merecemos un cambio, una oportunidad para tratar de cambiar las cosas y tener un mejor futuro para la familia de uno.

Alba, muchas gracias por estar dispuesta compartir tan abiertamente tu historia con nosotros.

Aquí están unas fotos de Honduras: un niño que trae la leche a las casas y una panadera que hace panes que se llaman “polvorones” y “tortas,” y unos niños jugando fútbol.

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Alba Guevara (English version)

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Alba Guevara

1. Tell us a little bit about yourself.

Okay, my name is Alba. I have three children. I’m from Honduras. What more can I say? I work. I’m a single mom. I like to spend time with my family, with my children. I like to be at home. I adore being at home. I like to go out and do my hobby, shopping, (laughs) but I don’t do it anymore. And I like the beach, that is what I like most, apart from shopping, and that’s it, spending time with my children.

2. What made you decide to do this interview?

Because I like sharing things about myself. Maybe other people are in the same situation as me or have gone through the same thing as me, and well, I don’t know, they don’t talk about it or they can’t talk about it. And, that’s why.

3. Where are you from and why did you decide to come to America?

I’m from Honduras, and the decision to come here wasn’t exactly mine, but rather, my mom’s. I didn’t know it, that I was coming over here. And one day she told me that my sister wanted to talk with me, that I should call my sister, and I spoke with her, and she told me a date. It was like about a month away, or I don’t remember when, and she said to me, “This date, the 16th of September, I’m coming for you in Guatemala. Get ready, and I will pick you p there.” Well, I had wanted to come over here when I was really little, like 13 years old. My sister had gone over there but my mom didn’t let me come at that time. And when I was pregnant with Nohelia, she told my sister to come for me. And that was for the best, having come.

4. What was life like for you where you grew up?

Well, it was difficult, very difficult, but, compared with our neighbors, it was different for us. They were in a worse situation than the one I grew up in. Really hard, but compared to the neighbors, well, it was not as bad, but I didn’t, well, my mother decided for me to come. So, I was pregnant and she told me, “You’re going over there.” And I think that was the best, because Nohelia was born here and I don’t know what might have happened if she was born over there. Maybe I would have come and she would have stayed and I wouldn’t have been able to bring her. Maybe she wouldn’t have been able to come until years later, until I would have been able to do my papers. It was good, having come when I was pregnant with her.

5. What is life like for people in your country now? Do you still have family and friends there?

Yes, my parents are there. There’s more family, a lot of family, on my dad’s side. The people of Honduras are very poor, that’s stayed the same. Nothing has improved. It is a country very behind, very poor, and every time I go over there it is very difficult because I don’t like it anymore. I’m not used to being there; I feel desperate being over there. And, I don’t know, I’m used to living here. Life here is different. Compared to over there, it is more comfortable being here. Well, you have to work a lot but it is safer. Safety is much better here than over there.

6. What did you have to do to get here (i.e. paperwork, money, etc.)?

Well, money, because I didn’t have papers. I entered illegally. In that time, ’96, I entered illegally here. Compared with other people who have entered, mine wasn’t so hard because my sister brought me. She picked me up in Guatemala and I came with her. We didn’t pay any coyote or anybody, just the two of us came. So she looked for help during the entire journey from Mexico, for people to give her directions. We traveled in a small car and she would pay someone to bring us to certain places, for the directions and everything. So, it wasn’t so bad. I was pregnant and even with all that, the journey wasn’t so bad. I didn’t walk and it was very safe because I didn’t come with a coyote, which is so dangerous. I didn’t walk at all, and I came in the car with my sister until we arrived at the border. She came because it was time for her ticket to get into California, and she left me there with her mother-in-law, the mother-in-law of my other sister, and then they helped me cross, some little kids helped me cross. It wasn’t so hard. I feel like back then it was easy, and now it’s hard. 18 years ago it wasn’t so hard, I think. Now it’s dangerous, more dangerous than in that time. I don’t know how much money they paid for me to cross; I didn’t pay anything. They, my sisters, paid for me. They did that for me.

7. Once you came to America, what was life like?

Recently arrived, it was difficult, mainly because, well, I didn’t have papers, I was pregnant, and then my daughter was born about a week of being here. A week after having arrived, she was born and it was very difficult. When I arrived in California it was very difficult because I couldn’t obtain health insurance, not for me, not for her, for my birth. She was born and they denied me. Then later I moved to New York, three months after she was born. When I moved to New York, then things began to change. There I started to work and it changed a lot. I found more help for illegal people in New York. I feel that in this state they really help people who don’t have papers. And I was there, illegal, without papers, and there I could get help for my expenses, like feeding my little girl. They gave me public assistance. In California I couldn’t even have Medicaid. In New York they gave me all that. I felt like there it was easier and I couldn’t live in California for that reason. In New York things were easier for me.

8. What helped you get to where you are today?

The one who has especially given me a lot of support is one of my sisters, my oldest sister. She was the one who brought me from Honduras. She is the one, in everything, is always keeping an eye on me, even when I got separated. Economically she has helped me a lot. She is always looking out for me. When I am unsure about making a decision about something, she gives me ideas and asks me, “Do you think that would be good?” She supports me. Of the family, of the sisters, she is the strongest. She has been through many things. She is the one who always stands up for everything. She is the one who always, when something happens in the family, is the one who we always talk with about things. And she is supportive through all things. She is one of the people who has motivated me when I have been sad, shattered. She talks to me and is a great support. And my children, who are the motors of my life.

9. How do different generations in your family experience America (i.e. immigrant-born vs. American-born generations)?

Well, it is very different, a lot of difference. When one is raised there, it is another type of upbringing, another culture, many things. Here children have more; that is what I have seen. They are freer to express themselves; they aren’t so submissive, they have more freedom. The kids, I don’t know, grow up better here. In everything, because compared to how I grew up there, how my parents grew up there, the difference is huge. When I went with my children to Honduras, they saw everything you see over there. They were scared by what they saw, by what there is, the poverty that’s there, the difference. He went, my son, and he really likes to play football. He had to take off his shoes to play like the other kids because they don’t have shoes for playing. And he wanted to do that, too, because he wasn’t going to play with shoes when the other kids didn’t have any. That was one of the things that he saw, that they don’t have shoes. He says they didn’t have clothes to wear, two changes of clothes and nothing else. What is here and what is over there is very different. The food over there is not so abundant, and here, well, food is left over. I think that, I don’t know, there are people that say that here they’ve gone hungry but I don’t think so, because here if you go to a church, they give you food. I’ve gone hungry recently when I got separated. I won’t forget it. We spent two weeks without food, without anything. I went to a church over here, and they gave me food and that’s how we made it. But compared to the hunger that you stand over there, which is a real hunger, a hunger of not having anything, it doesn’t compare.

10. Have you preserved any traditions, foods, languages, or customs from your native country?

Yes, we always speak Spanish here at home. It is very infrequent that we speak English. We eat foods like we ate there. I’m used to making food, the food that we eat in Honduras, like beans, rice, just like we eat them there. I don’t eat tortillas but the kids do. We eat cheese, cuajada (curd), mantequilla (Honduran sour cream), and food in the same way as I cooked it there. Green bananas, plantains. For us bananas and plantains are different, they are different things. Ripe plantains or green ones, or green bananas, is what we eat, tajadas (sliced). I’ve always been used to making them at home; we don’t change a thing. Traditions. Like what we make for holy week, we traditionally eat dry fish for holy week, so I always make that. For Christmas I make tamales, it is what we traditionally make in Honduras, and the food we make during that time, that I always keep making.

11. How does your cultural heritage affect your views on immigration?

In understanding what’s happening and what has always happened around immigration, why one comes, making the decision to come, to risk one’s life. Including the people who bring their small children, and they bring them risking their lives, no matter what happens, many things, things might happen to them. But I see that is by necessity, that they bring them, because life in Honduras isn’t easy. And maybe it’s the same in other countries, too. Not just in Honduras but also in other countries, and they bring their children because they want something better for them. And if they bring them over here, here they will be better, and they will be better with their family members, they will be more saved. And it’s bad that people think the opposite, that maybe the kids from there are coming to do things they shouldn’t do here, that they are people that are no good to live in this country. But, that’s not always true, not everyone is the same, there are all kinds, and the majority of them are coming because of necessity, to find something better, for the lives of these little children. I think that all of us deserve an opportunity and a better life, and they are looking for something better for those children.

12. Anything else you would like to add to the end of the interview?

For people to be conscious, that life in one’s country isn’t so easy. It is very different for the people who live here or that maybe have never lived away from here, that they haven’t suffered problems, hunger, danger. It is very difficult for those of us who have been raised in other countries, in such poor countries like Honduras. We know what happens there, how you live there, how difficult it is to be able to survive with so much danger, with so much hunger, so much need. It is different, right? The other side of the coin there, here, and maybe there are people who don’t know anything about this, maybe they think the opposite because they haven’t lived what one has lived, what one has been through. And I think that’s why they think that way. We all deserve a change, an opportunity to try and change things, and to have a better future for our family.

Ms. Guevara, thank you so much for being willing to share so openly about your story.

Here are some photos of Honduras: a boy that brings milk to the houses and a baker making breads called “polvorones” and “tortas,” and some kids playing soccer.