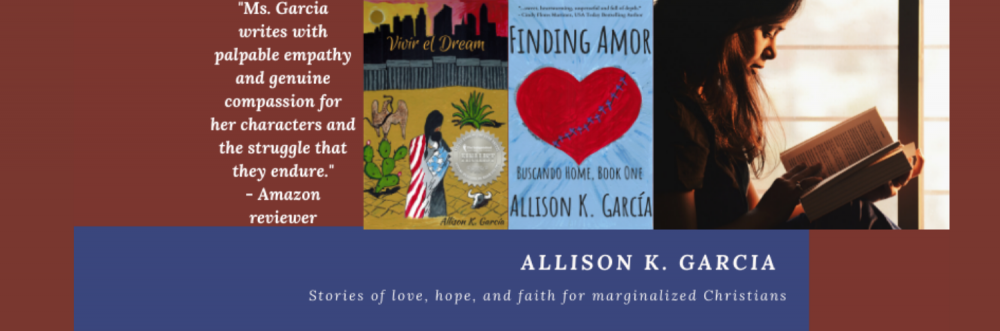

Check out what inspired me to write my book, Vivir el Dream.

Tag Archives: immigration

Vivir el Dream

Featured

Hello, everyone,

In case you hadn’t realized, I wrote a book and published it on May 19th! It is called Vivir el Dream and is a Latino Christian fiction book about an undocumented college student trying to make her way in the world.

You can find it on Amazon for $16.99 in paperback, $3.99 in ebook. Also signed copies are available for $15 (plus $3 shipping if you’re not local).

I was inspired by my friends, family, church family, and community who haven’t given up even when they’ve been through unimaginably difficult circumstances. I wanted to give a glimpse into the life of undocumented people in the U.S.: why they come here, what they have to go through to get here, and what things are like for them once they arrive.

It is also rich with descriptions of authentic Mexican cuisine and culture and has elements of inspiration, light romance, and humor.

You can also find out more information on my Facebook author page and on the Facebook book page.

Here’s a little more about the book:

The fates of an undocumented college student and her mother intertwine with a suicidal businessman’s. As circumstances worsen, will their faith carry them through or will their fears drag them down?

Linda Palacios crossed the border at age three with her mother, Juanita, to escape their traumatic life in Mexico and to pursue the American dream. Years later, Linda nears college graduation. With little hope for the future as an undocumented immigrant, Linda wonders where her life is going.

Tim Draker, a long-unemployed businessman, has wondered the same thing. Overcome with despair, he decides to take his own life. Before he can carry out his plan, he changes course when he finds a job as a mechanic. Embarrassed about working at a garage in the barrio, he lies to his wife in hopes of finding something better.

After Juanita’s coworker gets deported, she takes in her friend’s son, Hector, whom her daughter Linda can’t stand, While Juanita deals with nightmares of her traumatic past, she loses her job and decides to go into business for herself.

Will the three of them allow God to guide them through the challenges to come, or will they let their own desires and goals get in the way of His path?

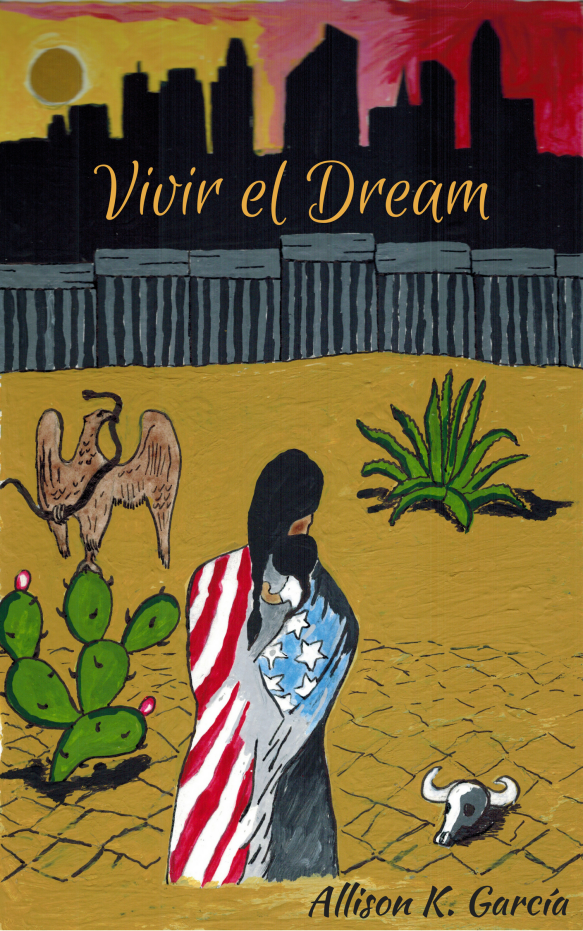

COVER REVEAL: Vivir el Dream

Vivir el Dream, my Latino Christian fiction novel, is set to release on Amazon in book print and ebook on May 20th.

It’s been over five years and literally thousands of hours of work to get it ready for this moment. And it’s starting to feel real! I got the cover, I’m picking out dingbats and fonts for formatting, and I’m only six chapters away from the end of the final edit. One day soon I will hold the completed book in my hand (I’m sure there will be a post for that day as well!)

I am thankful for my husband for painting the picture for my cover. He did an awesome job! 🙂

If you want to follow what’s going on with my book more closely and find the buy links, head over to my Facebook author page.

An Important Visualization

Today I would like to you in a guided visualization, one that I hope will help broaden your understanding and increase your empathy.

I would like you to remember a younger you, living in your hometown. If you lived several places, pick the place that felt most like home, where your family and friends lived. If that is where you live now, just picture that.

I want you to picture your favorite places there: your favorite restaurant, your favorite park, your home, your place of worship, your local supermarket, your school. I want you picture your family and friends. I want you to picture your time with them: the laughs you had together, the vacations you took, meals together, how you spent summers or your free time, even the fights you had and the tough times. Picture it in detail…the sound of their voices, their laughter, the way they held themselves, what they wore. Use as many senses as possible.

Once you have a vivid picture in your mind, think about how you felt back then. How much like home it feels. Perhaps you even still dream of these people and places. They are an essential part of you. You cannot remove these things from you. They feel like home, no matter if they were challenging times or not.

Now I want you to imagine that things went a bit different. I’d like you to imagine that that place that you call your hometown was going through a rough time, that there were no jobs available or the jobs there couldn’t pay the bills. Imagine that your family had to make tough choices…sell the family car(s), get rid of cable/internet/phones, live somewhere less expensive (and most likely more dangerous), never go to your favorite restaurant again, never go on vacations, never participate in your favorite hobbies due to lack of funds and transportation, leave school to work at an early age to support the family, not be able to go to your place of worship because you had to work extra overtime to put food on the table, having to decide whether to cut off water or electric or both in order to feed your family. Really think about it, what it would feel like to live, not just paycheck to paycheck, but going to bed hungry and worrying that you wouldn’t make enough to save your family. If you really want to go the extra mile, picture a huge increase in violence in the area, maybe even war, due to the extreme poverty.

Now imagine that you’ve heard of a place, where a lot of other people from your hometown were moving. A place where people lived comfortably, where they had food to eat and safe places to live, where you could send your future children to school, where you could make enough money to send back to your family so that they would have food on the table and a safe place to live. Think about how strong your desire would be to move to this place, how desperate you might feel to go there.

Imagine this place was hard to visit, not to mention move to. Imagine the system was corrupt and all the official were corrupt, that your family and friends have tried to pay the little money they had, only to be rejected a visit and not returned their “filing fees.” Think about how it would be to decide to hitch a ride with someone who knew a way to get you in. You might make that choice even if you had to scrounge all the money you could to get there, in risk of your own life, just on the offchance that you could save your family from poverty. Imagine you make it, while others around you have died in the desert that separates your hometown and that place. Imagine how scared you would still feel that you could get caught at any time but how glad you would be to be able to send money to your family. You wouldn’t be able to go home and visit your family but you could speak with them on the phone and send them money so they would be safe.

Let’s say you didn’t want to take that chance and somehow, through a modern miracle, you were able to legally get a pass to live in that better place. This way you are able to travel when you can save enough money and go back and visit your family. They are living, still poor, but safe and fed.

Either way, imagine you have been living this way for years. Imagine you have established a life in the better place. Imagine you have family and friends there, a home, a favorite restaurant/grocery store, maybe even a hobby or two. Picture it well, with all your senses. You miss your hometown but you also have a life in this new place.

Imagine that things haven’t been as easy as you expected in the new place. There is a lot of hatred towards people from your hometown and people give you looks when you walk down the street, hold their purses closer/lock their car doors as you walk past them, keep an eye on you as you shop. You’re used to it but it seems to be getting worse because a new leader has come on the scene, and he has called people from your hometown rapists, murderers, criminals, “bad people”, and has promised to build a giant wall to keep out the people from your hometown. Imagine this new leader has promised to deport people back to their hometowns, even ones that have passes, even ones that have never lived there. Imagine he has said that he will deport your son or daughter who was born in the new place. This new leader has encouraged anger and violence against your hometown and other towns outside of the region. Imagine that more than half the people you thought were friends and family and community voted for this man to be the leader of the new place. Now you don’t know who to trust anymore. It no longer feels safe here and it starts to feel less like home, but you have a family here, a life. There is nothing you can do. You are only a regular, working class person, trying to survive and keep your family safe and fed.

Imagine how this feels. Really feel it. REALLY feel it.

Because this is how immigrants are feeling right this second.

And this is how I, the wife of an immigrant and the mother of the child of an immigrant, am feeling right as I finish this blog post.

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Entrevista con Nínive

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Entrevista con Nínive

- Dime un poco acerca de ti.

Mi nombre es Nínive, estoy casada con un americano y tengo dos hijos. Hasta hace 3 años, mi familia y yo vivimos en mi país trabajando con CRU (Cruzada Estudiantil y Profesional para Cristo).

- ¿Por qué decidiste tener esta entrevista?

Porque me gustaría que más gente sea expuesta a la historia detrás de cada inmigrante.

- ¿De dónde eres y por qué decidiste venir a los Estados Unidos?

Soy de Venezuela, y decidí, junto a mi esposo, venir a vivir a los Estados Unidos en busca de mejores oportunidades para mis hijos, quienes tienen necesidades especiales.

- ¿Cómo era la vida para ti donde creciste?

Mi vida fue difícil. Mi familia es grande y por esa razón llena de muchos secretos e historias de las que casi no se habla. Cuando tenía 5 años mi madre adoptiva falleció y desde entonces, mi hermanito y yo, fuimos a vivir con una tía. Con ella sufrimos muchos maltratos. Años más tarde fuimos a vivir con mi abuelita y las cosas mejoraron un poco. Crecí con mucha escasez, pero dentro de todo mi vida fue mejor que la de mis hermanos biológicos. Todas mis hermanas biológicas fueron madres adolescentes y ni siquiera terminaron la preparatoria.

- ¿Cómo es la vida para tus paisanos ahora? ¿Todavía tienes familiares y amigos allá?

Toda mi familia sigue en Venezuela, soy la única aquí. La vida para ellos es aún más difícil ahora. En estos momentos Venezuela vive uno de los períodos más difíciles de su historia. No hay comida, y la poca que hay está siendo racionada. La delincuencia y el índice de criminalidad se han elevado en extremo. Tenemos una inflación del 62%. No hay trabajos y los salarios son muy bajos.

- ¿Qué tuviste que hacer para llegar aquí (como documentos, dinero, etc.)?

Porque mi esposo es ciudadano americano, aplique por una visa de inmigrante. Era la única manera de venir a este país. El año anterior, me fue negada la visa de turista, aún cuando demostré que mi intención no era la de inmigrar. El proceso fue largo, costoso y agotador. Mi experiencia con inmigración no fue buena. Todos mis papeles se perdieron por más de un año. Ni siquiera aparecía en el sistema. Después de un año de estar en el país, me dijeron que yo no existía, era como si nunca vine a los Estados Unidos. Finalmente, después de involucrar a un Senador del estado recibí mi Green card y podia trabajar.

7. Ya estando en Estados Unidos, ¿cómo fue tu vida?

Muchas cosas han cambiado, lo más difícil ha sido adaptarme a la cultura sin perder mi identidad como venezolana y tratar de mantener un balance de las dos culturas en casa. Otra cosa difícil ha sido el idioma y las expectativas que otros tienen sobre eso. Soy muy directa y por eso tengo mucha dificultad en expresar mis pensamientos sin ofender a otros. Mi vida aquí es más tranquila, no voy caminando por la calle con miedo y sé que mi familia tiene lo necesario para vivir y alimentarse.

8. ¿Qué te ha ayudado llegar a dónde estás hoy?

Primeramente Dios, Él me ha fortalecido en el proceso de adaptación, en buscar ayuda para nuestros hijos. También el apoyo de mi esposo y de la Iglesia.

9. ¿Cómo experimentan las generaciones diferentes en tu familia los Estados Unidos (como los que nacieron en su país comparado con los que nacieron en los Estados Unidos)?

Esa ha sido la parte más difícil con mi familia. Especialmente mi hija, aunque nació aquí, vivió en Venezuela hasta los 5 años. Ella ha olvidado el español y ha perdido mucho de su identidad como venezolana. Es difícil mantener un balance cuando dentro de la misma casa tienes las dos culturas. Mi esposo abraza mi cultura y tradiciones y hasta el idioma, pero es difícil pasar eso a nuestros hijos cuando el resto de sus familiares, amigos y maestros no tienen esa identidad.

10. ¿Has preservado algunas tradiciones, comidas, idiomas, o costumbres de tu país natal?

Sí, usualmente cocino comida venezolana, que a mi familia le gusta. Mi esposo y yo hablamos español casi todo el tiempo. Tratamos de hablar y exponer a nuestros hijos a sus raíces hispanas mostrándoles fotos, videos, escuchando música. Incluso vamos al servicio en español de nuestra iglesia y así mantener el compañerismo con otros hispanos. Para mi es importante que mis hijos sepan de donde vienen.

11. ¿Cómo afecta tu herencia cultural tus ideas sobre la inmigración?

Definitivamente está afectada. Es imposible ser inmigrante y no ver el es tema desde tu perspectiva cultural. Venir de una cultura donde todos son aceptados sin importar su color de piel, su nacionalidad, su acento o su región, hace difícil no tener una posición radical hacia la injusticia del sistema migratorio. Pero creo que se hace más fuerte, a causa de las opiniones y críticas infundadas de ciudadanos americanos, que parecieran olvidar la historia de su país. Esta es una nación fundada en la inmigración, que buscaba la igualdad de su gente, la libertad y la justicia, tristemente para muchos, América es de ellos y no hay cabida para otros, especialmente si se ven diferente y hablan otro idioma.

Esto entristece mi corazón porque mi propia familia es una mezcla de las dos culturas y es como si una parte de ella debería ser anulada. Aunque mi situación migratoria es diferente a la de muchos, debo incluirme cuando digo que no hemos venido a quitarle nada a nadie. Venimos a trabajar, a buscar un futro mejor. Muchos vienen huyendo del crimen, de la pobreza, de la falta de comida, no vienen a pedir vienen a dar. Ponen sus manos, su sudor para que otros tengamos comodidades que muchos de ellos no tienen.

Debo dejar claro, que si bien es cierto que muchos piensan todas esas cosas de los inmigrantes, Dios me ha dado la bendición de conocer gente que abraza y apoya a quienes vienen de otros lugares y sus culturas!

Gracias, Nínive, por compartir tan abiertamente su historia con nosotros.

Y aquí comparte unas fotos chéveres de su país y familia:

una foto del barrio en el que crecí! Allí vive mi abuela y otros familiares!

Una foto de mi abuelita, si Dios quiere este año cumplirá 90 años. mi familia

mi familia Caracas

Caracas universitarios

universitarios la selva en Venezuela

la selva en Venezuela Los Andes

Los Andes una playa venezolana

una playa venezolana el desierto

el desierto

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Nínive

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Nínive

- Tell us a little bit about yourself.

My name is Nínive, I’m married to an American and have two kids. Until 3 years ago, my family and I lived in my home country, where we worked with CRU (Campus Crusade for Christ)

- What made you decide to do this interview?

Because I would like more people to be exposed to the story behind every immigrant.

- Where are you from and why did you decide to come to America?

I’m from Venezuela, and decided, with my husband, to come to the USA looking for better opportunities for our kids, who have special needs.

- What was life like for you where you grew up?

My life was difficult. My family is HUGE, and for that reason it is full of secrets and stories that nobody talks about. When I was 5 years old my adoptive mom died and my little brother and I went to live with an aunt. We suffered abuse. Years later we went to live with my grandma and things started getting a little bit better. We didn’t have much, but I can say that even with all the bad stuff in it, my life was a lot better than my biological siblings. All my sisters were teen moms and they didn’t even finish High School.

- What is life like for people in your country now? Do you still have family and friends there?

All my family is still there. I’m the only one here. Life for them is even harder now. Venezuela is experiencing the toughest times of its history. There are food shortages, and the little one can find is being rationed. Crime and delinquency have increased sharply. Inflation this past year just reached 62%. There are no jobs and salaries are very low.

- What did you have to do to get here (i.e. paperwork, money, etc.)?

Because my husband is an American citizen, I applied for an immigrant visa. It was the only way to come to this country again. The year before I was denied a tourist visa, even when I demonstrated that it wasn’t my intention to immigrate. The process was long, expensive and exhausting. My experience with immigration wasn’t good. All my papers were lost for more than a year, I wasn’t even registered in the system. After spending more than a year in the country I was told I didn’t exist; it was like I never came to the USA. Finally, after getting a Senator from Virginia involved, I got my green card and was able to work.

7. Once you came to America, what was life like?

Many things have changed; the biggest challenge has been adapting to this culture without losing my identity as a Venezuelan and trying to balance two cultures in our home. Another difficult thing has been the language and the expectations of others concerning this. I am very direct and as a result it is hard to express my thoughts without offending others. My life here is more tranquil, I have no fear walking outside, and I know my family has what we need to live and eat.

8. What helped you get to where you are today?

First of all, God. He has strengthened me during the process of adapting, as we have sought help for our children. Also the support of my husband and the Church.

9. How do different generations in your family experience America (i.e. immigrant-born vs. American-born generations)?

That has been the most difficult part for my family. Especially with my daughter, who was born here but lived in Venezuela until she was 5 years old. She has forgotten her Spanish, and has also lost much of her identity as a Venezuelan. It is difficult to maintain a balance when there are two cultures in the same house. My husband embraces my culture and traditions, even my language, but it is difficult to pass that on to our kids when the rest of their relatives, friends and teachers don’t have that identity.

10. Have you preserved any traditions, foods, languages, or customs from your native country?

Yes, I often cook Venezuelan food that my family enjoys. My husband and I speak Spanish almost all the time. We try to talk with and expose our kids to their Hispanic roots by showing them pictures, videos and listening to music. We even go to the Spanish service in our church and keep the fellowship with other Hispanics. For me, it is very important that my kids know where they come from.

11. How does your cultural heritage affect your views on immigration?

Definitely it is affected. It’s impossible, as an Immigrant, to not see this issue from your cultural perspective. When you come from a culture where everybody is accepted without looking at the color of their skin, their nationalities, their accents, or the region that they came from; it makes it difficult not to have a radical position about the injustice of the immigration system. But I think that what makes it even more difficult are the critical and unfounded opinions of many Americans, who seem to forget the history of their Nation. This is a Nation founded on immigration, seeking for its people equality, liberty and justice. Sadly, for many America it’s theirs and there is no place for others, especially if they look different and speak a different language.

This makes me sad because my own family is a mix of both cultures, and it seems to me, like one of those parts needs to be annulled. Even when my immigration status is different, I have to include myself when I say that we didn’t come here to take anything from anybody. We came here to work, to seek a better future. Many come here escaping from crime and violence in their countries, escaping from poverty, because they don’t have money to feed their families. We come here not to ask for a handout but to give. They offer their hands, their sweat, so we can have things that they themselves cannot even afford.

I also need to clarify, that even when it is true that many people in America think this way, God has given me the blessing of allowing me to meet many people who embrace and support those who come from other places and other cultures.

Nínive, thank you so much for openly sharing your story with us!

And here are some pictures she has shared with us, too!

(the barrio where I grew up and a lot of my family, including my grandmother still live)

(A photo of my grandma. God willing, she will turn 90 this year)

(A photo of my grandma. God willing, she will turn 90 this year)

(Caracas)

(Caracas) (my family)

(my family) (the desert in Venezuela)

(the desert in Venezuela) (Venezuelan beach)

(Venezuelan beach) (the Andes mountains)

(the Andes mountains)  (the jungle)

(the jungle)

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Rocio Watson

I was nine years old when we left Mexico. I love my country. I didn’t want to leave, but we had to. My dad had been a student organizer for many years in the 60s. During that time, student organizers started “disappearing” so many had to go to into exile to save their lives. Somehow he didn’t have to escape back then. Later, when I was nine, he started teaching in the University, someone recognized him, and he was threatened.

I remembered one day, I was so young, my mom talking to him and crying and she said, “We have to go.”

At that time, I didn’t understand why we had to leave. “We have to go where?” I asked.

“We have to go away” is what she told us.

We just all got on a plane; we had passports and visas. My dad was already in the States, working for a banking institution. My mom tried to protect us and said, “We’re just going to stay with dad for a while.” But we never came back.

(My grandparents, my brothers and cousins at their 50th wedding anniversary. I am the child in the light blue dress on the far right. This picture was taken a few days before we moved to the U.S.)

I’m the oldest of five. For me and my brothers and my little sister, it was fun. We though, “We’re going to go to Disney Land” and stuff like that, but actually my dad had some distant relatives who lived in Anaheim, California who took us in. But they weren’t the nicest people, and they would make comments that I was not able to understand. They were very derogative. They would make comments, “Why are these wetbacks here?” and “Why don’t they just go back to where they came from?” At the time, I found such comments odd, since they too were immigrants who like my father had left their homeland for hopes of providing a better life for their family. Besides, they were family and isn’t family supposed to help each other?

Then, my father, who is a university grad, who is a professor, has to take a job at the Marriot as a busboy, under the radar, to take care of his family and keep us safe.

“What’s going on?” I kept wondering. I love my country, my cousins; we never went without, we were fine. I was very resentful. And I thought, “Why are we here when the people are treating us like we were lesser than?” At the time, I was nine years old, and I could not understand why my father had brought us to a strange place, taking away from our family and support system. I was resentful and often ask my parents, “Why are we here? We couldn’t we have gone somewhere else?”

We stayed in Anaheim for a few months until my dad was fed up, and we moved into this small apartment with my grandma, who had also been threatened. We are grateful we never had to go through crossing the dangerous border, the way so many of our brothers and sister immigrants do. Risking it all, with the hope of escaping violence, abuse, poverty and political corruption. Being so young, I simply could not understand.

(My brother an I at 5 and 3 years old in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico)

My dad worked; my mom took care of us. In spite of everything, all his hardships, you would think he would’ve been bitter, but my dad never complained. He worked his butt off, and he was always so genuine and sweet. We were the only Mexican family in a predominately Caucasian neighborhood. Just looking at us, nobody would have known; we were all fair-skinned. But the fact was, we didn’t speak English. Whenever people would ask why we didn’t speak English, my dad, would say something like, “That’s because we’re from Mexico” in broken English. He was always so welcoming to everyone. He would tell the neighbors, “Come, come eat.”

One time my little sister was going to be baptized, and we had a full-on Mexican party in our fenced in suburban front yard, and everyone kept looking. My dad said, “Come here, come here, you want a taco?” And that’s how we grew up. We didn’t feel like we were any different than anyone else. In fact, we celebrated where we came from.

It wasn’t until I went from high school that I realized I was any different. Kids would ask really inappropriate questions, even teachers really crossed the line. Saying, things like, “Is it true that you Mexicans don’t flush the toilet?” which I would often answer with anger and resentment by saying, “What? What are you talking about? Of course we flush the toilet.”

When I entered school, even though I had phenomenal grades, somebody took it upon themselves to put me in ESL classes. I was in remedial reading and ESL, and I thought, “What the hell am I doing here?” Coming where I was coming from, I asked one of the teachers, “Why am I here?” Then I spoke with one of the counselors, who said I needed to test out of ESL, so I took the test and I passed it. But being in those classes, I had made friends with all these other Latino immigrant kids and so I said to them, “Hey, they are holding us back. You have to take this test. We’re going to pass, and we’re going to show these people.” So, one day, they all came to my house and studied hard and all of them took the test. Only one kid did not pass. Then all of a sudden, I was persona non grata among the school’s administration.

In the meantime, I noticed there were a lot of more immigrant kids coming in to the school, so I went to the administration and said, “Hey, you owe it to these kids to create a support system.” And I remember the vice principal said, “You think so? Then you create it.” So, I did, pretty soon there was a solid group of 6 or 7 brave Latino immigrant students who were banding together to make sure everyone had a fair chance at a good education and a safety net of support.

Back then the school had assemblies, rallies, for the local teens, and they used to have these talent shows but they were all in English. Quickly, our school was about 47% Latino, so I went and talked to the administration, and as soon I walked into the office, I could see the look in their faces, I knew that they were probably thinking, “Here she comes again, when she is going to graduate?”

Once in the office, I said, “We want our own talent show or want to be incorporated in yours”. Reluctantly they agreed to allow us to put together our own talent show and we created this play all in Spanish.” Once, we had everything we needed for the show, I went back to the office and asked the administrator for a time and date to showcase our play. They said it was fine and that they would pull the Latino kids out of class and have them go. And I said, “No, it needs to be open to everybody, just like your rally is open to everybody else.” So, once again they said yes, and there were about 1,100 kids that came to watch our play. It was so empowering. And not just for the Latino immigrant kids but it helped the other immigrant kids, realize that they too had a right to belong and empower them to be proud of who they were. We were all immigrant kids victims of a corrupt world that forced our families to have to leave the comfort of their beloved homeland.

It just kind of carried on through high school and then in college, I was really interested in human rights and law. I went to school for criminal justice; I wanted to be a prosecutor. During my senior year, I interned at the local county Victim Services and Advocacy Program I was one of two only Spanish-speaking people, and I was assigned to the sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse unit, which was very challenging. I grew up in a good home with loving parents. I had no idea what a problem that was in our Latino community, and I just thought, “What is this?”

I excelled in my internship and made some very good contacts. My assigned mentor and deputy district attorney took me under her wing and helped me grow professionally. She continuously pushed to be a better public servant and to take calculated risks. My job as an intern was to prepare the prosecution witnesses; my job was to encourage them to cooperate and to tell them that it was ok to tell the truth. In informed them of their rights and advised them that if they fear for their safety we could relocate them to a safe environment. Soon, I became very successful with helping these folks be empowered to tell their story.

Then, my career took an unexpected twist and through our county court house, I met a judge whose mom happened to be Mexican and whose dad was Scandinavian. He had presided over several of my cases and I had become impressed at his discipline and search for justice. This judge was now planning on stepping down from the judicial bench and decided to take a chance at running against the local county district attorney.

It just so happen that one of my mentors was running his campaign, and she said, “He really thinks highly of you, and we really want to reach out to the Latino community. If he makes it, he would like you to write a proposal to outreach and engage the Latino community.” I was 22, and I realized this is why my dad made the sacrifice, he made of leaving his country to give us a chance at a better life. Just like my dad, I took a chance and wrote a proposal, and when this judge was sworn in as the new county D.A. he made good on his word. I suddenly became the Latino spokesperson for the local County D.A.’s office, and in addition, I managed the Vietnamese outreach program as they were the second fastest growing immigration population in our county. I was 23 years old and really didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I just wanted my people to know that the law applies to everyone, not just people with papers.

In 1999, the local GOP chapter began, speaking out against the immigrant population and started putting a lot of pressure on the local authorities to act as sort of deputized immigration officers, due to this kind of political pressure there was a law passed in California that would look to prosecute anyone who utilized a fictitious social security number in their application for state IDs and driver licenses. This law mandated that everyone now had to carry a State I.D., and if your social security number didn’t check out during your application process, you were automatically arrested for providing false information. That did not sit well with me, given that I too was an immigrant. After all we were not talking about common criminals; we were talking about good people, like my dad, who were only trying to raise their families in a better and safer environment.

I went to my boss and said, “Why are we being part of this unjust law?. My parents came here illegally and you know what they produced. They produced good kids who serve and are productive members of the community .I look at the very people our office is looking to prosecute as common criminals and I cannot in good conscience be part of an entity that is persecuting people like my parents.” I told him, “I can’t do this.”

By doing this, I knew I was putting my career in the local D.A.’s office in jeopardy, after all this, I was making very good money. I was only 25 years old. In addition, by being part of the criminal justice system made my parents proud. After all, I had managed to beat the odds, managed after lots of hard work I had accomplished at 25 years old, what other people had not accomplished in their mid-40’s. But, at the end of the day I felt like a hypocrite and a traitor for being part of what I considered a brutal and unnecessary assault on people’s inalienable and human right to make an honest wage and support their family. After all, I am the product of good immigrant parents and a contributor to my thriving new community.

After I said, what I needed to say, he looked at me and said, “I understand what you’re saying. I had family members from way back who did the same thing. Now, if you repeat this, I will deny it. I have hired people who are undocumented but the law is the law.”

I said, “So, Jim Crow was the law, slavery was the law, do you agree with that?”

“The law is the law,” he told me.

And I said, “Well, thank you for the opportunity. I appreciate it. You’re a good person, but you’re a politician, and I’m not. I’m leaving. We can spin this however you want. I want you to know that I’m leaving, because what you’re doing is wrong.”

And that was it; two weeks later I left the D.A.’s office and never looked back.

I won’t deny that this was a very hard decision, particularly because I was afforded such an amazing career opportunity at such a young age. In addition, I knew that the financial hit would be hard since I had financial responsibilities and creditors who didn’t care about my convictions or values, but just wanted to get paid. But, I knew that if I stayed there, it would be a slap in my parents’ and my people’s face. And with that I decided to start over, left my community and moved to another State to continue my education and to continue to find a more constructive purpose.

During my transition, I met a wonderful person who would later become my husband, and decided to continue on my journey to start over but knew to keep my options open. After three days of moving into my new community I found a job as a victim advocate at a local women’s shelter. Without hesitation, I entered into this new and sometimes intimidating phase in my career, the stories I heard from the amazing survivors opened my eyes and refocused my efforts into a new found passion. I found a way to be proactive instead of reactive, particularly when it came to violence against women and children, to me, by the time these case came to us at the prosecuting office, it was way too late, to mend the hearts and souls of these battered women and children. I immediately saw this as an opportunity, and as my new found my calling, to empower these survivors see that there’s a better way to live without the constant threat of intimidation and violence. I was spent about 7 months away from my friends and family, learning as much as I could from my new mentors, when suddenly I received a call from a former police detective who had too grown disillusioned with our judicial system and who now was a director at a women’s shelter. She shared that she was looking for a new outreach director and encouraged me to apply for the position. I took a leap of faith, took a deep breath and moved back to what had become my adoptive homeland.

Six months into my new role, the existing Executive Director of the organization made the decision to retire. I soon got a call from one of our board member, a county deputy prosecuting attorney whom I had met during my time with the prosecuting office, she encouraged me to consider taking on the role of interim Executive Director knowing my qualifications and I once again, took a leap of faith and grasped at the chance to continue to advocate for all survivors of abuse and violence.

I soon found myself running a shelter in for battered, human trafficking, and sexual assault survivors for 7 years. During my tenure with this wonderful and progressive organization, we were able to help hundreds of women and children, and even men.

After meeting and helping hundreds of survivors, we were approached by a local partner about possibly providing services to a male survivor of human trafficking. Our partner shared that he had attempted to kill himself and due to the fact that he happened to be a male survivor, he had very limited options since most shelters only providing housing to women and children. As a male survivor of human trafficking, his only options were homeless shelters, which were not able to provide the specialized advocacy and support that someone in his situation needed. After some discussion with our management team, we decided to take him into our program and put him up in an undisclosed hotel type facility with the goal of gradually assessing if he and our women survivors who were currently in our shelter could cohabitate in the same environment.

One of our male advocates who also had been a victim of child trafficking picked him up and after giving him a couple days to settle in, under close supervision, I showed up along with another colleague to introduce ourselves and our program.

At the time all we knew about him was that he had been a survivor of severe child abuse, trafficking and agonizing physical and mental torture. I can remember meeting him at the hotel where he was staying. He was short in stature, appeared to be in a daze after having been transferred by a hospital in Los Angeles where he had been placed in a 72 hour hold for attempting to take his own life having grown tired all of his suffering.

As we entered the room, we introduced ourselves and our programs. As we spoke my colleague and I quickly noticed, visible scars all over his arms, he simply looked defeated and exhausted. He shared he had been born in Oaxaca, Mexico. After our very short conversation, he politely but firmly said “say what you need to say and get out.”

I coincidentally, had just come back from Oaxaca and had absolutely fallen in love with its people and the culture. During my travels I picked a beautiful silver beaded rosary. I simply bought the rosary not for spiritual purposes but because of its beautiful designs and craftsmanship. I happened to be wearing the rosary that day, as we spoke; I soon noticed this survivor looking at my rosary and he said, that looks like to rosaries in Oaxaca, I then took the chance to share memories of recent trip there and saw that his look quickly soften. We then shared some delicious Oaxacan food from a local restaurant and the barriers between us seemed to fade.

I told him, “I understand you’ve been through something; I want you to know we’re here to help you.” We made light conversation for the next hour and I said, “Listen, we’ll be back. Please call us anytime if you need anything. We’re going to try to find you a place where you can be safe and comfortable.”

My colleague and I went back to the shelter and gathered our management team, I told them, “We have a male survivor who needs our help and if we are too stay true to our mission, then we must be prepared to help all survivors. I think he needs to be around people who can make him feel he’s not the only one. Why don’t we ask the women in our shelter how they feel about a male survivor being in the shelter, and we can base our final decision based on their input. And so we did.

Back at the shelter, we gather the women and informed them that he needed our help. We told the women, “Listen, this guy is just like all of you. He’s been victimized, and I hope you’d consider him as a fellow survivor and brother who needs help. We didn’t get into the specifics of his abuse as it was horrific.

Unanimously the women said, “We don’t have a problem, let’s help him.”

After our meeting, I drove to the hotel where he had been living for the past 3 days and told him about the shelter. Reluctantly he agreed to come with us and he was given a private room with a private bathroom.

During his stay in our facility, the transformation was obvious, he just blossomed. Everybody loved him. He cooked for the women, cleaned and was sweet and caring to all the kids. In a few months, we were able to legally certify him as a survivor of human trafficking and he was able to receive a special visa and work permit that allowed him to remain legally in the U.S. and work.

As time passed, this broken soul shared with us that his abuse began at the tender age of 7. He was abused by his father and his brother, who did whatever they wanted with him and sold them to whomever they wanted. After running away to escape his abusive environment, he went on to encounter further abuse by a man who posing as a good Samaritan offered him a place to stay. After hearing his story, I knew why he had lost his faith in humanity and that his healing journey would be challenging due to the horrendous abuse he had endured.

After completing his program and knowing how helpful he was taking care of our facility, he ended up being the house manager for our transitional housing program. For the first time in his entire life he was able to make his own decisions, earn a living and come home without the fear of exploitation and violence.

One day, I was walking through the hallways, and he said, “Quiero hablar contigo.” (I want to talk with you.)

We went to my office and sat down, and he said, “Can I sit close to you?” I said “sure and I sat in my office chair next to him. He then started to cry, and he said, “I just want you to know, that when you came to see me at the hotel, the whole time I was thinking, I don’t even what to hear what these women have to say, I’m done. I will be gone in a few hours. I’m not worth it. I don’t even understand who these people are and what their motive is for helping me. To be honest, I was planning to kill myself as soon as you ladies left me alone in that hotel room. Throughout you speaking to me, I can’t remember exactly what you said, but I remember looking at your eyes and feeling the sincerity of your words and for a moment I thought, maybe these people are real, and they’re going to help me, accept me and I’m going to be fine.”

Unfortunately his is one of many cases of the devastating effects of human trafficking, fortunately for this survivor he was able to find the opportunity and support system that helped him overcome his abusive past and start a new life.

He is one of the many survivors who left an indelible print in my heart and to this day, I consider him a friend and a beacon of light and hope for other survivors. I’m just in awe, not just of him, but of all the survivors I’ve met. I don’t know how they get through what they’ve been through; it’s just such a miracle. I don’t know how else to put it. To hear their stories and knowing where they’ve come from and seeing them overcome insurmountable obstacles and abuse is a tribute to all the brave and hardworking immigrants like my parents.

It was then and it is still, now my opinion that the tyranny of our current immigration laws allow and create an environment for the inhumane treatment of those who assume the risk of leaving their country and risking their lives for the hope of a better life and the opportunity to be able to earn an honest wage and feed their family.

I get very upset when I hear all these hateful and anti-immigrant conversations. These ignorant and hateful people claim that all of us immigrants are doing nothing but committing crimes, bringing diseases and mooching off the government. My own experience proves them wrong along with millions of stories of honest and hardworking immigrants who have earned everything they have with their sweat and tears.

To imply that all immigrants are here with the hope of sitting back and “mooching” off the government is not only offensive but frankly, enraging. I think about all of my years I have dedicated to helping all survivors of violence and think, what would have happen if I had taken a similar hateful attitude towards people who are different than me and said to them, “Oh sorry, you are part of my community, gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation; then I’m not going to help you.” After all we are all an integral part of our community we are people who have something to contribute and there is beauty in diversity. We are not illegal aliens, WE ARE HUMAN BEINGS!

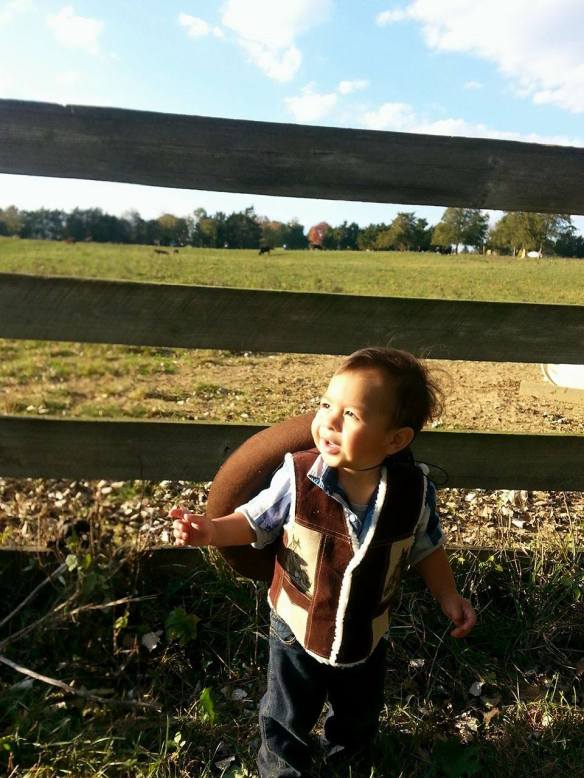

After 5 years of marriage and another relocation, my husband and I have settled in our new community, had a beautiful son and I now work with a non-profit organization that connects children with critical care in 8 different partner countries which includes central America and the Dominican Republic.

(My son, myself and my husband)

Against all odds, my parents have managed to raise 5 productive public servants who serve their community as best they can. In fact my younger, sister works for one of our members of Congress and is determined to continue to make our parents and people proud.

One of the greatest lessons I learned from my parents was to be of service. My parents would often say to us, “As immigrants and members of our new community we all have the responsibility to serve and give back.”

Through our immigrant experience, we were given an opportunity, to make our people proud, and to prove to those who hate us without knowing our stories and struggles, that we are an important part of U.S. history and like all human beings, simply want the opportunity to strive for a better life. To these hateful people I say, “We have earned everything we have and have worked tirelessly to serve our community without prejudice or hatred.

I hope that by sharing my story I can be part of the effort to continue to educate people about the immigrant struggle. I strongly believe that by sharing our stories, we can illustrate the beauty and importance of diversity.

(Mom & Dad’s wedding 1972)

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Paul L.

- Tell us a little bit about yourself.

I am Paul. I am nearly 42 years old and married. I live in historic Old New Castle in Delaware. I have worked most of the last twenty years in different facets of the medical field. I have had one of my short stories published, as of last year.

- What made you decide to do this interview?

I heard that Allison was doing this project and since my family isn’t very far removed from Europe I asked if I could participate.

- Where is your family from and why did they decide to come to America?

My father’s people are Irish Catholic. My grandfather’s people, on my mother’s side, were from Sicily. My grandmother’s people, on my mother’s side, were from Lithuania. As far as I know, they came here to escape different types of oppression: Organized crime in Sicily, the Russian overlords in Lithuania, the fighting with the Protestants in Ireland.

- What was life like for them in “the old country”?

As you can see above, it wasn’t too easy for them back at home so they risked all to come here.

- What did they have to do to get here (i.e. paperwork, money, etc.)?

I believe that they all came through Ellis Island. Two out of the three families had their last names permanently altered there, I’m told that this was a common occurrence.

- What hardships did they face coming to America?

There was still massive discrimination against the Irish. You may see those antique signs that read, ‘IRISH NEED NOT APPLY’? They weren’t antiques then. My Irish grandmother did find work in a leather-cutting factory that has long since been torn down. My great grandfather, from Lithuania, rode a horse and buggy to get around and sold moonshine out of his still to supplement his income.

- Once they were in America, what was life like for them?

It was hard at first but they not only adapted but thrived. My great grandfather, from Lithuania, bought a large patch of land in South Jersey and farmed it. My great grandfather, from Ireland, was a stone mason. Back then the names and designs on gravestones were chiseled by hand and he was one of the last true masters at it.

- How did different generations experience America (i.e. immigrant-born vs. American-born generations)?

My great grandfather, from Sicily, was sad to find that some of bigger cities in America, at the time, were just as corrupted by organized crime as the country that he left for that same reason. My mother was discriminated against in her small hometown in South Jersey because she was ‘mixed’! Lithuanian AND Italian, can you believe that?

- Did your family pass down their native tongue or preserve any cultural traditions, foods, or customs?

My grandparents were the last to be able to speak the native tongue fluently. There is the Italian tradition of gathering on Christmas Eve and eating fish. None of us really liked fish so we gathered and had pasta. 10. How many generations later did you arrive? I’m third generation American, on all counts. 11. Does knowing your cultural heritage affect your views on immigration? I’m very aware of my roots. I went all through school with other kids who had the same story as I. We were almost universally three generations removed from Europe. We were almost all: Irish, Italian, Polish, German, Russian, British, Scottish, French etc.or some mixture of those. Once I got into the world outside my community I found that a lot of people, my age and younger, were so removed from the ‘old country’ that they didn’t even know what they were. They have NO idea about the hardship of those that came before them. I guess what I’m saying, what I know to be true is that the more things change the more that they stay they same, yes? 12. What else would you like to share with everyone about yourself, your family, or about immigration in general? All good things that I am are because of them. They taught me how to be physically and mentally strong. They taught me that fear, any and ALL fear, can be completely conquered. They also put Jesus in my heart. For all this I am eternally grateful. 13. Paul, thank you so much for being willing to share so openly about your story. It was an honor and a pleasure.

Allison, this is a picture from a funeral in the 1920’s. The man and woman are my great grandmother and great grandfather. The three children are my great aunt, great uncle, and my grandmother Mary, on my mom’s side. This picture was taken at their hog farm in South Jersey. The baby in the casket was never named. They were originally from Lithuania.

Here are a couple pictures from Paul and his family at his wedding to his lovely wife, Valerie. 🙂

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Norys

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Interview with Norys

“Giros” by Norys (fabric art)

- Tell us a little bit about yourself.

My name is Norys, and I’m the oldest of three siblings. I’m also a student of medicine and agricultural engineering. I’ve lived here for almost eight years and am still trying to adapt to the culture and the system in general.

2. What made you decide to do this interview?

I believe it is important so people know who we, the immigrants, are and that we have a voice and story to tell.

3. Where are you from and why did you decide to come to America?

I’m Salvadoran and I didn’t make the decision, my parents did. They thought that here I would have a better future.

4. What was life like for you where you grew up?

Beautiful! Even though there were limitations, we were free. There was not enough food or money. We had meat only on special occasions. I had a lot of friends and every moment with them was like creating a movie. Those are happy memories. What I want to say is that we lived; we lived. It was happier. It didn’t matter if there was no money or if there was no food, it was the spirit of happiness that kept us alive.

5. What is life like for people in your country now? Do you still have family and friends there?

Yes, most of my friends are in El Salvador, my paternal grandparents and my grandmother on my mom’s side and my aunt. It’s still the same, only with the different that it is not the same El Salvador where I grew up; there is more fear, more violence, and more insecurity. It’s still beautiful with its scenery, its culture, and its people, but it’s not the same.

6. What did you have to do to get here (i.e. paperwork, money, etc)?

I crossed the border like most do. It was an unknown and dangerous journey. It took me three weeks to arrive at my destination. You didn’t know if each day that ended would bring another tomorrow. It is like a horror movie. You don’t know what is coming next. It is unknown, horrible. If they asked me to do it again, I wouldn’t do it.

7. What hardships did you face coming to America?

I think that the hardest thing of the journey was everything together, starting from leaving my land. Upon leaving my house, I said, Norys, don’t look back and keep going. So, that was the hardest part, leaving my land, my people. Once I began the journey I was confronted with other difficulties like traveling with strangers. You didn’t really know what type of people were traveling with you, if they were good or if they were bad. There were moments in which I had to console people who wanted to commit suicide and be there and tell them that this was going to pass, that we weren’t going to stay there forever, that it was going to pass. Trying to save my own life and save the lives of others was difficult but it gave me the strength to go on.

(here is a video of the following end of the question, it is in Spanish but you can follow along…the answer starts around 0:15)

One person cut his veins because he didn’t want to leave his grandchildren. And he lost a lot of blood so the guide asked if anyone knew how to put in an IV. And, well, no one is prepared for something like that. In a journey like that it would be really lucky for a doctor or nurse to come, but this time there wasn’t anybody. Seeing the need, and being a student of medicine, I said that I would do it, it was something I had to do. So I said I could do it, I could try. And that person was lying on a dirt floor, and he was white, like paper, and I did the procedure and I don’t know how I did it but I did it, and he lived. He lived and I don’t know what happened with him later but then another woman got like this, like an anxiety, and she got really bad, because the experience, itself, is traumatic. No one is prepared for what comes on the journey. Once on the journey you don’t know how the mind will react. So this person, she said that she didn’t want to live anymore, that she didn’t want to live anymore, but she had two twin daughters that she left behind in El Salvador, and she had told me about them when we met for the first time and had told me that she left behind her family. So I told her, “You have to live. You have to get to this country so you can work and bring your daughters so you can be together, and you can’t think negative. Who will take care of your daughters if you die or if you do something crazy? Who will see after them? So I had my fears, and I had my fears because it was an unknown journey and everyone will tell it differently depending on how they lived it but this is how I lived it. And so I had to put my fears to the side so I could try to be a help to these people and I didn’t mind, I didn’t mind. I lost my fear ad I said, these people need me more, and well, I did that, and I believe that’s what gave me the strength to get through that journey, that uncertain journey, and arrive at the destination. Like the fear of those people helped me to overcome my own fears and therefore be able to help them. You never know when…we all have our fears because it’s a natural thing, right? But seeing that many others were more afraid, then yours becomes insignificant and you can say, “oh, that is nothing, but this is serious. They really need help.” And that’s when you do something, when you give.

8. Once you came to America, what was life like?

My life in the United States. (sigh) It was difficult to adapt, I think it’s like that for everyone. With something new, if you’re afraid, it’s natural. The fear of the unknown. But to me, time passes that you start to adapt and you begin to not be yourself because you have to follow patterns. Like the ones that are already here, they say, “Hey, they do things this way.” Then you follow that same pattern. But after a while you get involved in the system, you change opinions, and you begin adapting your own ways. Another hard thing was learning the language. Going to school when you’re 21 and being around kids that are 14, 15, 16. That was a challenge, but once I arrived here my father told me, “If you going to be in this country, without knowing the language, you’re nothing.” And he was right. I went to school for four years and I graduated with my high school diploma for the second time, and I accomplished it. And now I say, knowing the language has saved my life. It has opened doors for me and I have met a lot of people, I have been to places, that if it weren’t for knowing the language, I don’t know, it never would have happened. Going back to high school and pretending that you’re a certain age when you aren’t is hard. Pretending was hard. For me. But, I had to do it; I had to do it. I’m an introverted person so I got through this time unscathed because I didn’t talk, I only learned and analyzed and observed and I didn’t have the need to say, “Oh, I’m 21 or 22.”

And coming here and being a single mother. To come carrying a baby in your womb and go to school, be a single mother, adapt to the system, a new culture, it was the complete package. It was hard. It was hard but here I am.

9. What helped you get to where you are today?

The worst that can happen to someone is dying. While you’re alive, there are many possibilities, and I believe being 29 years old is a blessing, because in my country, life is no longer worth anything. Then waking up the next day and seeing the light is like, thank you, right? For another day. And to know that everything passes, sadness passes. There will always be a new day. Like I said before, while you’re alive, there are many possibilities. The opportunities are there, it’s only having the desire to look for them. To dream. I am a dreamer and I dream big. I always say, everything happens for a reason. We are here and I am here with a purpose. I am here for a reason. I don’t have everything I want but I have everything I need. You understand? So I think that is what’s most important. Not looking back but rather continuing and continuing and knowing that one day you’re going to be there, where you have always dreamed.

10. How do different generations in your family experience America (i.e. immigrant-born vs. American-born generations)?

The new generations don’t have a sense of culture. When I say that, I feel that they don’t have culture, it is a double culture. Finally, it’s like saying, “Am I American or am I Salvadoran?” What is there in the middle? Then it’s what is there in the middle, it’s what has been lost. The old generations or the older generations, like my parents, my aunts and uncles, cousins, they have that history, they have that folklore still in them, but here they have forgotten to pass it on to these new generations. So it gets lost. They have become Americanized, forgetting about their roots, of that rich folklore that we have as Salvadorans. I’m talking about the rest of my family. Personally, I try to continue cultivating that, that spirit, that culture. I try to cook with those same aromas and pass on that culture to my daughters. And it is difficult when you are married to a person who shares a different culture. Balancing both cultures is hard.

I am trying to continue speaking Spanish, continue cooking those traditional dishes, and continue saving those traditions. In my family I feel it has been lost, because they say, “We are in America, we will live like Americans.” Okay. There’s nothing bad in that but I feel it is important that our children, as Latinos, as the Hispanic-Americans we are, it is important that they know their roots, where they come from. For me it is important, because I want them to have the same feeling, the same love for their roots. It doesn’t matter how nice or ugly El Salvador is. It doesn’t matter how violent it is. That folklore and that human charm will always prevail. It will always be there and just because a group of people are doing bad, doesn’t mean that our children shouldn’t know where their mother and father come from, you know? They have to have that, because it doesn’t matter where they are, if they’re here or in China, they have to know what their roots are.

11. Have you preserved any traditions, foods, languages, or customs from your native country?

Yes. I am writing a book of traditional recipes. I love the kitchen. It is a form of transmitting life and bringing memories. I like cooking and sharing how I do it. Sharing the recipe and say, for example, on holy week, it’s a custom in El Salvador to make fish tortas, and I love them. I remember how my paternal grandmother made them, and I have it etched in my mind and I remember that she would be there in the kitchen and she would said, “Don’t stick your hands in the dough. Don’t touch.” So then I’d only observe but I observed with detail and that how I make them now; it is how I cook. So that’s what I’m doing, preserving, I could say, the recipe as much as the memory, of how I learned to make it and pass it on. Then when I am cooking, I am telling the story, and she was like angry. She didn’t like me to be in the kitchen, but unconsciously I was learning, unconsciously she was teaching. So that is how I learned.

12. How does your cultural heritage affect your views on immigration?

It’s complex. Just the word immigration is like, “ouch.” The system is unjust. Just the fact of crossing borders and adapting ourselves to a culture that’s no our own, is a big change. Aside from that, dealing with a immigration system that doesn’t help, but rather destroys, emotionally and culturally, I think there’s a lot to say and even then it’s not enough.

We aren’t here to be pitied, but it would be good to be accepted for who we are and what we can contribute to the development of the country, bring a little of our culture and share. Originally, this country was built by immigrants. So it doesn’t have a specific culture, if you could say that. There is a diversity of cultures. Why can’t we join each other and celebrate life and celebrate diversity? All of us would be happier and everything would be easier. While we create barriers that you’re white and you’re black, red, yellow, there will always be conflict and nobody will ever be happy. What can’t we all love each other just like we are?

13. What else would you like to share with everyone about yourself, your family, or about immigration in general?

About me?…um…I believe my message would be like this: while you’re alive, there are many possibilities, and it doesn’t mater where we find ourselves. If we are in this place, it’s because we have to be here for a purpose, and independent of what we believe, we have to get out, search, and fight for our dreams. And even though the system or society where we live is unjust, it’s not a reason to say, “I can’t.” Society does not have to accept us. There is a strong reason why we are here “now.” It doesn’t matter where we are. Like I said, the system doesn’t work for us, we don’t have to adjust, but we have to critique and we have to fight. We have to make them know that we have a voice and that we have a story to tell.

Norys, thank you so much for being willing to share so openly about your story.

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Una Entrevista con Alba Guevara (versión en español)

Walk a Mile in Their Shoes: Entrevista con Alba Guevara

1. Dime un poco acerca de ti.

Okay, mi nombre es Alba. Tengo tres hijos. Soy de Honduras. ¿Qué más puedo decir? Trabajo. Soy mamá soltera. Me gusta pasar tiempo con mi familia, con mis hijos. Me gusta estar en casa. Adoro estar en casa. Me gusta salir a mi pasatiempo, salir de compras, (se ríe) pero ya no lo hago. Y me gusta la playa, eso es lo que más me gusta, aparte de hacer las compras, y eso, pasar tiempo con mis hijos.

2. ¿Por qué decidiste tener esta entrevista?

Porque me gusta compartir cosas mías. Tal vez otra gente está en la misma situación mía o ha pasado lo mismo que yo, y, pues, no sé, no lo dicen o no lo pueden decir. Y, por eso.

3. ¿De dónde eres y por qué decidiste venir a los Estados Unidos?

Soy de Honduras y la decisión de venir acá no fue precisamente mía, pues, mi mamá. Yo no lo sabía, que venía para acá. Y un día ella me dijo que mi hermana quería hablar conmigo, que le llamara a mi hermana y hablé con ella y ella me dijo tal fecha. Era como, faltaba, no sé, un mes, o yo no recuerdo cuando, y ella me dijo, “Esta fecha, el 16 de septiembre, voy por ti a Guatemala. Alístate, que yo te recojo allí.” Pues, yo había querido venirme para acá cuando estaba bien pequeña, como de 13 años. Mi hermana había ido para allá pero mi mamá no me dejó venir en este tiempo. Y cuando ya estaba embarazada de Nohelia, ella me habló a mi hermana que fuera por mi. Y eso fue por lo mejor, haberme venido.

4. ¿Cómo era la vida para ti donde creciste?

Pues, fue difícil, bastante difícil, pero en comparación con los vecinos que teníamos, era diferente a la de nosotros. Ellos estaban en peor situación a la que yo me crecí. Bastante difícil pero a comparar con los vecinos, pues, no era tanto, pero decidí, pues, no lo decidí yo, fue mi mamá que decidió que viniera. Pues, estaba embarazada y ella me dijo, “Te vas para allá.” Y pienso que fue lo mejor porque nació Nohelia acá y no sé que hubiera pasado si ella hubiera nacido allá. Quizás me hubiera venido y ella se hubiera quedado y no la hubiera podido traer. Quizás hasta que yo pudiera hacer mis papeles ella hubiera podido entrar años después. Eso fue bien, haber venido cuando estaba embarazada yo de ella.

5. ¿Cómo es la vida para tus paisanos ahora? ¿Todavía tienes familiares y amigos allá?

Sí, están mis papás. Hay más familia, bastante familia, por parte mis papás. Las personas de Honduras son bien pobres, eso sigue igual. Nada ha mejorado. Es un país muy atrasado, muy pobre, y cada vez que voy para allá es bien difícil porque ya no me gusta. No me acostumbra estar allá, me desespera estar allá. Y, no sé, me acostumbré vivir acá. La vida acá es diferente. Compararla con la de allá, está más cómodo, estar aquí. Pues, hay que trabajar bastante pero es más seguro. La seguridad es mucho mejor acá que allá.

6. ¿Qué tuviste que hacer para llegar aquí (como documentos, dinero, etc.)?

Bueno, dinero, porque papeles no tenía. Entré ilegal. En este tiempo, ’96, entré ilegal acá. A comparación con otras personas que han entrado, lo mío no fue tan difícil porque mi hermana me trajo. Me recogió en Guatemala y con ella vine. No pagamos ningún coyote, ni nadie, sólo íbamos nosotros dos. Pues ella buscó ayuda allá en todo lo que fue el viaje de México, que le dieran direcciones las personas. Viajábamos en un carrito pequeño y ella le pagaba a alguien que nos llevara a tal lado por direcciones y todo. Pues, no fue tan malo. Yo venía embarazada y a pesar de todo eso, el viaje no fue tan malo. No caminé y fue muy seguro porque no me vine con coyote, que eso es tan peligroso. Yo no caminé nada y vine en carro con mi hermana hasta que llegamos a la frontera. Ella se vino porque era el tiempo de que tenía su boleto que tenía que entrar por California, y me dejó allí con la suegra de ella, la suegra de mi otra hermana, y luego allí me pasaron, unos muchachitos me pasaron. No fue tan difícil. Siento que en ese tiempo fue fácil, y ahora está difícil. Hace 18 años atrás pienso que no era tan difícil. Ahora está peligroso, más peligroso que en este tiempo. No sé cuanto dinero pagaron ellas por que me pasaron, yo no pagué nada. Ellas, mis hermanas, pagaron por mi. Ellas hicieron eso por mi.

7. Ya estando en Estados Unidos, ¿cómo fue tu vida?

Recién llegué, fue difícil, porque lo principal, pues, no tenía papeles, embarazada, y luego nació mi niña a la semana de estar aquí. La semana de haber llegado nació ella y muy difícil. Cuando llegué a California fue muy difícil porque no pude obtener el seguro médico, ni para mi, ni para ella, para mi parto. Ella nació y me lo negaron. Entonces luego me mudé a Nueva York, a los tres meses de ella haber nacido. Cuando me mudé a Nueva York, allí cambiaron ya las cosas. Allí empecé a trabajar y cambió bastante. Encontré más ayuda para las personas ilegales en Nueva York. Siento que en este estado ayudan mucho a las personas que no tienen papeles. Y estaba así, ilegal, sin papeles, y allí pude obtener ayuda para mis gastos, como darle a comer a mi niña. Me dieron asistencia pública. En California no pude tener ni el Medicaid. En Nueva York me dieron todo eso. Sentí que allí fue más fácil y no pude vivir en California por esa razón. En Nueva York me facilitó más las cosas.

8. ¿Qué te ha ayudado llegar a dónde estás hoy?

En especial, quien he tenido mucho apoyo es una de mis hermanas, mi hermana mayor. Fue la que me fue a traer a Honduras. Es la que siempre está pendiente de mi en todo, aún cuando me separé. Económicamente me ha ayudado en mucho. Ella está muy pendiente de mi. Cuando estoy indecisa de tomar una decisión de algo, ella me da ideas y me dice, “¿Tú crees que eso sería bien?” Ella me apoya. De la familia, de las hermanas, ella es la más fuerte. Ella ha pasado muchas cosas. Ella es la que siempre da la cara por todo. Es la que siempre, cuando pasa algo en la familia, es la que siempre estamos hablándole para algo. Y ella apoya en todo. Ella es una de las personas que ha motivado a mi cuando yo he estado tristeza, derrumbada. Ella me habla y es un gran apoyo. Y mis hijos, que son los motores de mi vida.

9. ¿Cómo experimentan las generaciones diferentes en tu familia los Estados Unidos (como los que nacieron en su país comparado con los que nacieron en los Estados Unidos)?

Pues, es muy diferente, mucha diferencia. Cuando uno se crece allá, es otro tipo de enseñanza, otra cultura, muchas cosas. Aquí los niños tienen más; eso es lo que yo he visto. Están más libre de expresarse, no son como más sumisos, están con más libertad. Los niños, no sé, se crecen mejor acá. En todo, porque a como me crecí allá, como mis papás se crecieron, es mucha la diferencia. Cuando fui con mis hijos a Honduras, ellos ven todo lo que se ve allá, que se quedan asustados por lo que ven, por lo que hay, la pobreza que hay, la diferencia. Él fue, el varoncito, y él sí le gusta jugar fútbol. Él tuvo que quitarse sus zapatos, sus tacos, para jugar como los demás niños porque ellos no tienen tacos para jugar. Y él lo quiso hacer así también porque no iba a jugar él con zapatos, con tacos, cuando los niños no tenían. Eso es una de las cosas que él vio, que no tienen zapatos. Él dice que no tenían ropa para vestirse, dos mudadas que traerse mas nada. Eso es mucha diferencia a lo que es aquí a lo que es allá. La comida que allá no es tan abundante, y aquí, pues, sobra la comida. Pienso que, no sé, hay gente que dice que aquí aguantan hambre pero yo pienso que no, porque aquí si uno va a una iglesia, le regalan comida. Yo pasé por hambre recién que me separé. No se me va a olvidar. Pasamos dos semanas sin comida, sin nada. Yo fui a la iglesia que está acá y allí me regalaron comida. Fue difícil, dos semanas sin tener nada que comer nosotros en casa aquí, nada. Pero a mi me regalaron comida y eso nos alcancemos. Pero comparado a la hambre que se pasa allá, que es hambre, hambre de no haber nada, no se compara.

10. ¿Has preservado algunas tradiciones, comidas, idiomas, o costumbres de tu país natal?

Sí, hablamos español aquí en casa siempre. Es muy poco lo que hablamos en inglés. Las comidas lo comemos como allá. Yo acostumbré a hacer la comida, la comida que comemos en Honduras, como los frijoles, el arroz, así como comemos allá. Tortillas yo no como pero los niños sí comen. Comemos el queso, la cuajada, la mantequilla, y la comida igual como la cocinaba yo allá. Los guineos verdes, los plátanos. Para nosotros es diferente los guineos con los plátanos, son dos cosas diferentes. Plátanos maduros o verdes, o los guineos verdes, es lo que comemos, tajadas. Eso siempre lo acostumbré en casa hacer; no cambiamos nada. Las tradiciones. Como lo que hace para semana santa, nosotros acostumbramos a comer pescado seco para semana santa, eso lo hago siempre. Para Navidad hago tamales, es lo que se acostumbra hacer allí en Honduras, y la comida que hacemos para en ese tiempo, eso siempre lo sigo haciendo.

11. ¿Cómo afecta tu herencia cultural tus ideas sobre la inmigración?

En lo que está pasando y que ha pasado siempre acerca de la inmigración, porque uno se viene, tomar la decisión de venirse, arriesgarse. Incluyendo las personas que traen a sus niños pequeños y que traen a arriesgarlos, a lo que pase, las cosas, que les pase algo. Pero yo veo que es por necesidad, que lo traen porque la vida en Honduras no es fácil. Y tal vez en otros países también, no sólo en Honduras sino otros países, y ellos están trayendo a sus hijos porque quieren algo mejor para ellos. Y si los traen para acá, ellos acá estarán mejor y estarán con sus familiares, estarán más salvos. Y eso está malo de que las personas piensen todo lo contrario, de que tal vez vienen los niños de allá que tal vez vienen a hacer las cosas que no deben de hacer acá, que son personas que no son buenas para vivir en este país. Pues, no siempre eso es cierto, no todas las personas somos iguales, siempre hay de todo, y la mayoría vienen por necesidad, por buscar algo mejor, para la vida de esas criaturas. Pienso que todos merecemos una oportunidad y una mejor vida, y están buscando algo mejor para esos niños.

12. ¿Algo más que te gustaría añadir al fin de la entrevista?

Hacer conciencia a las personas, de que la vida en los países de uno no es fácil. Es muy diferente a las personas que vivimos acá o que tal vez nunca han vivido fuera de acá, que no han pasado problemas, de necesidades como de hambre, de peligro. Es muy difícil tal vez en lo que hemos crecido en otros países, en países muy pobres como Honduras. Sabemos lo que pasa allá, como se vive allá, lo difícil que es para poder sobrevivir con tanto peligro, con tanta hambre, tanta necesidad. Es diferente, ¿verdad? La otra cara de la moneda allá, acá, y tal vez hay personas que no saben nada de eso, tal vez piensen todo lo contrario porque no han vivido lo que uno ha vivido, lo que uno ha pasado. Y pienso que por eso esos piensan de esas formas. Todos merecemos un cambio, una oportunidad para tratar de cambiar las cosas y tener un mejor futuro para la familia de uno.

Alba, muchas gracias por estar dispuesta compartir tan abiertamente tu historia con nosotros.

Aquí están unas fotos de Honduras: un niño que trae la leche a las casas y una panadera que hace panes que se llaman “polvorones” y “tortas,” y unos niños jugando fútbol.